WWPH Writes Issue 107…and we are excited to share: We now have a YouTube channel, which showcases a special program from our 50th anniversary event. We are still buzzing about this celebration held last month at The Writer’s Center in Bethesda. Take a look here at readings with Grace Cavalieri, E. Ethelbert Miller, Erika Raskin, Kathleen Wheaton, and poet-performing artist Aris.

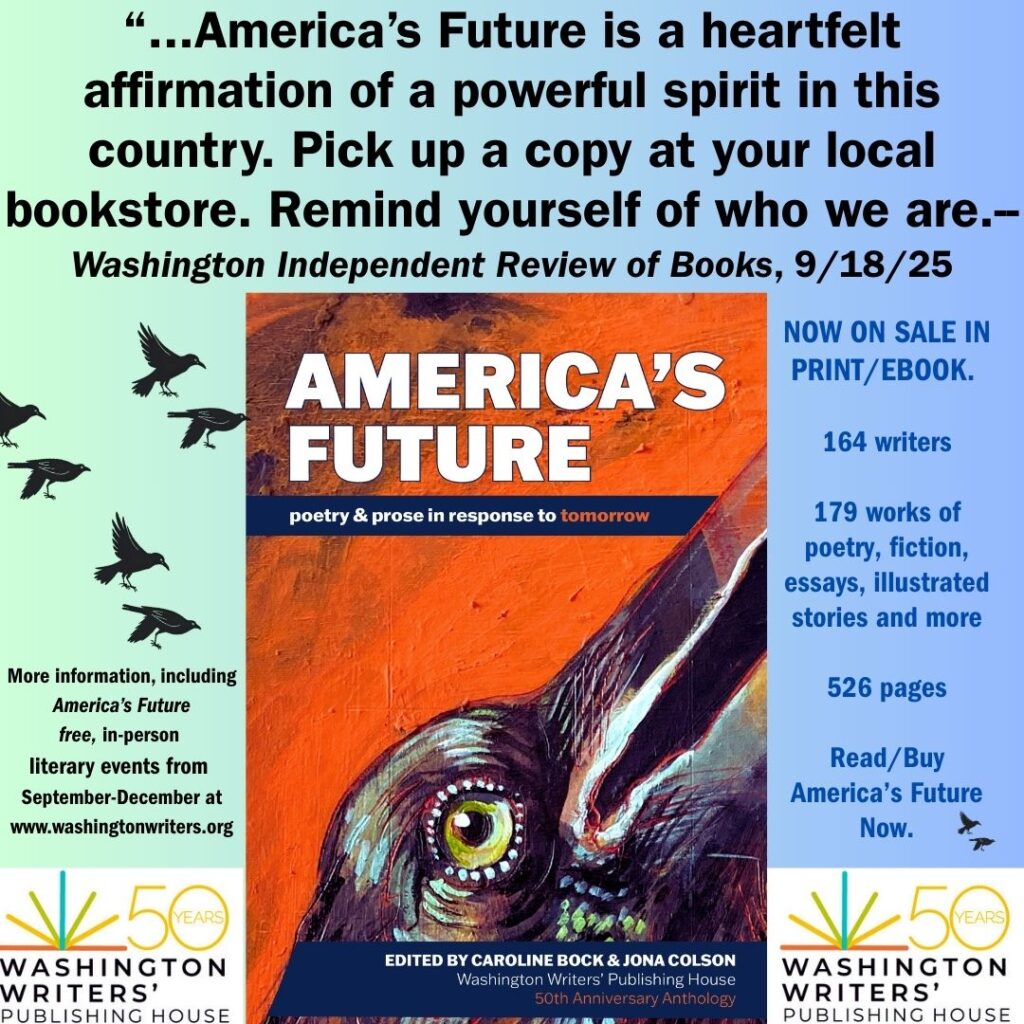

We also have samplings from our big/bold new anthology, AMERICA’S FUTURE, posted from a cross-section of writers in the collection here, too. We had a lot of fun producing these with Jon Gann of ReelPlan and are so grateful to all the writers who participated. Watch them now!

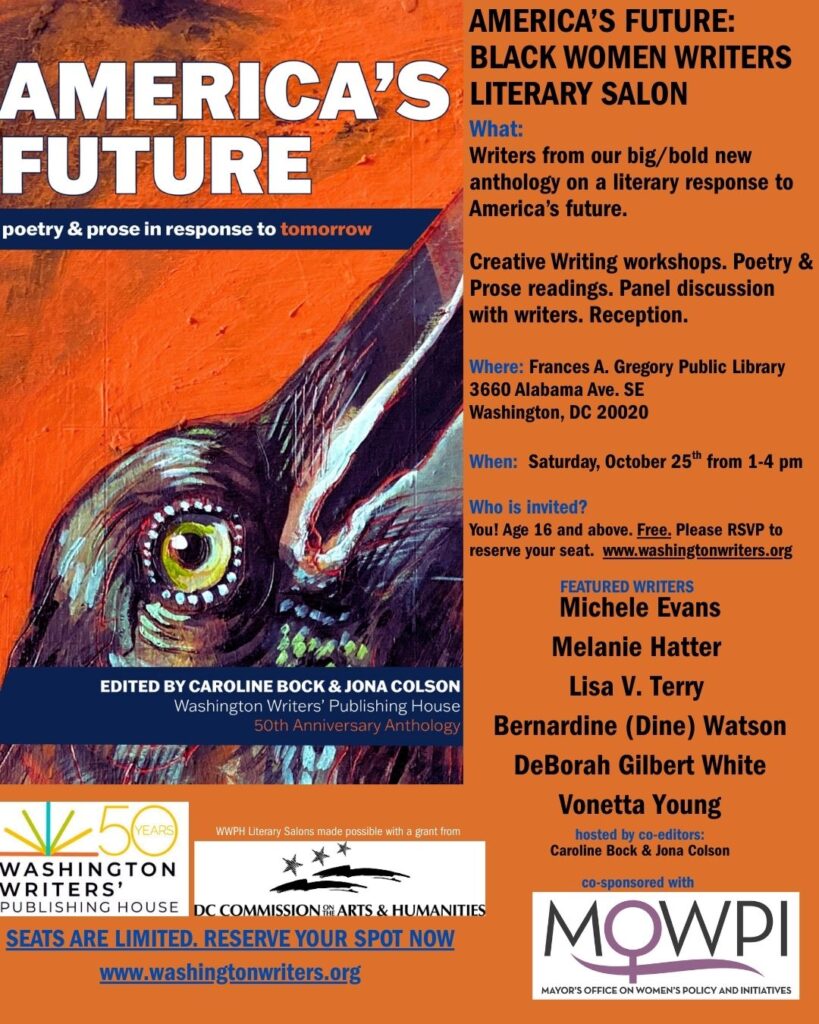

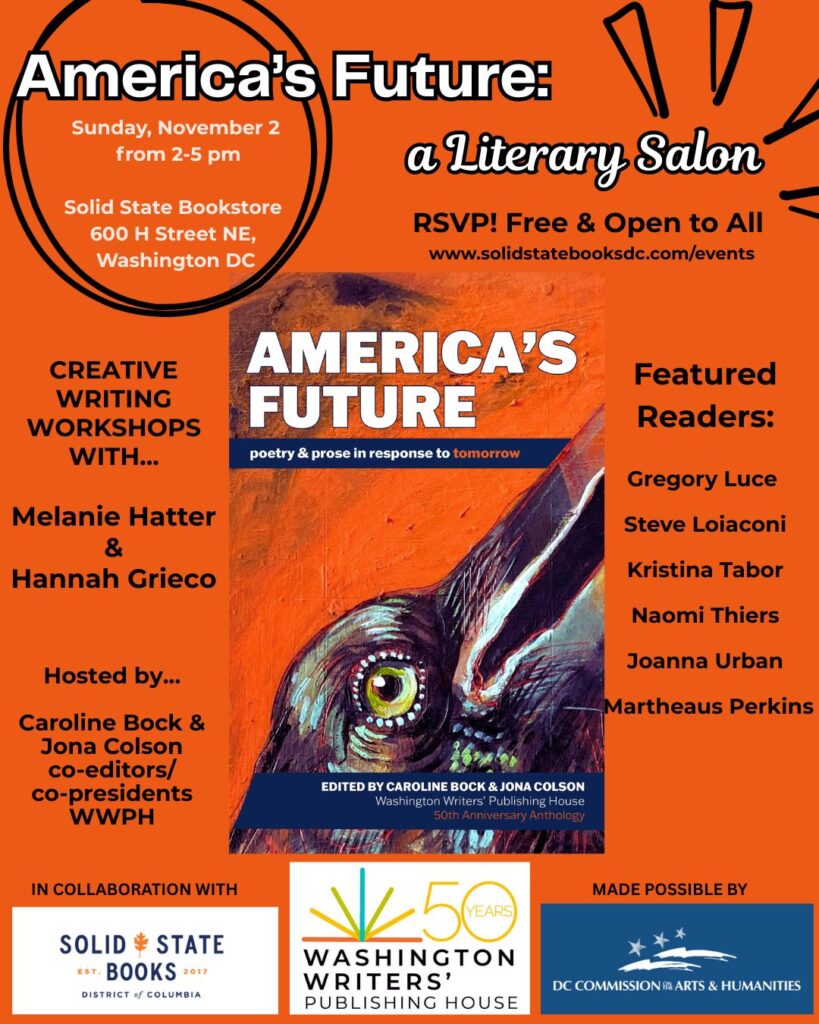

We are thoroughly enjoying meeting so many of you at our America’s Future reading events and literary salons, and we’re not stopping now. See below for more details on the events scheduled for October. All our free and open.

Last and not least! We are featuring three writers–Gregory Luce, Peter Philipps, and Eben Atreyu Bracy (the latter is a must-read for baseball fans!) in this issue.

Read on!

Caroline Bock & Jona Colson

co-presidents/editors

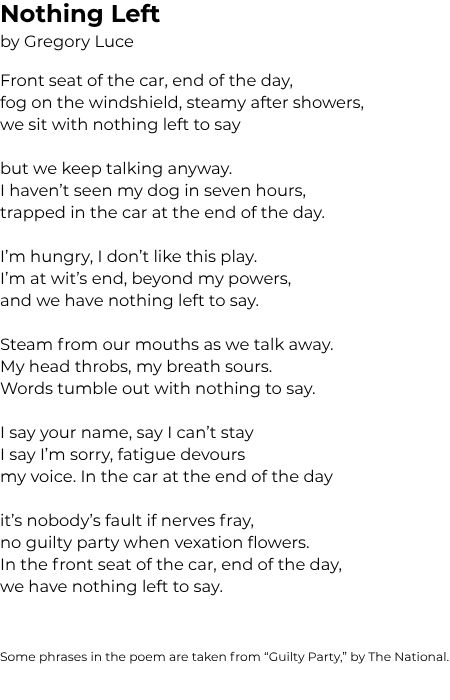

WWPH WRITES POETRY

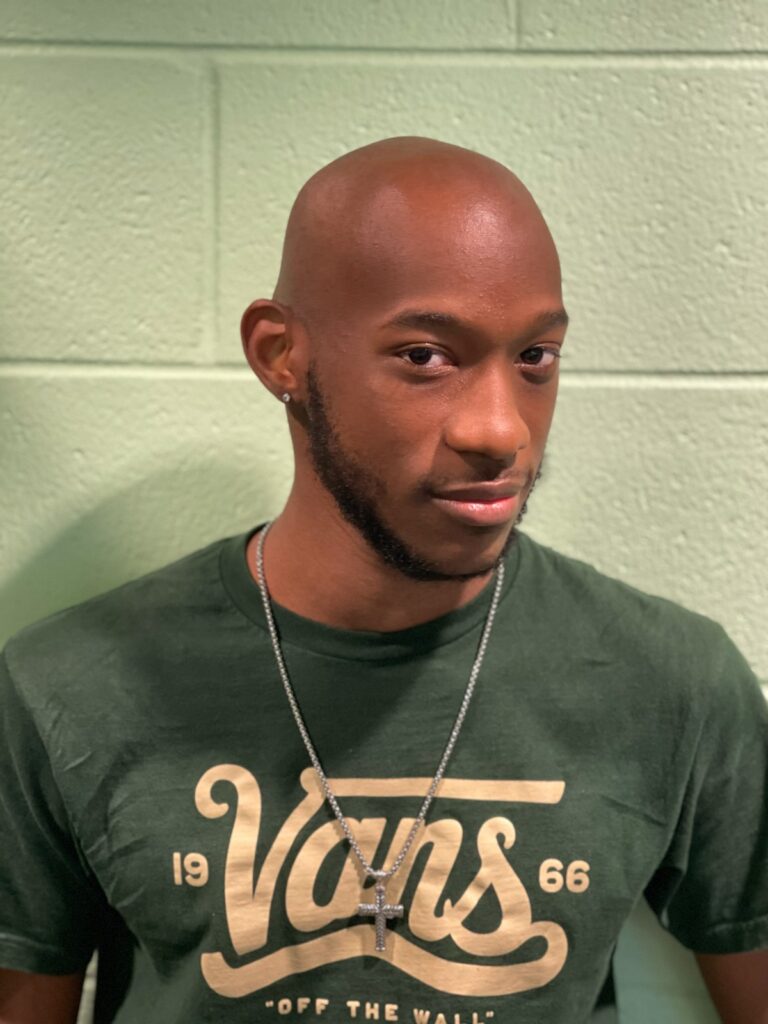

Gregory Luce is the author of five books of poems and has published widely in print and online. In addition to poetry, he writes a monthly column of the arts for Scene4 Magazine. Retired from National Geographic, he is a volunteer tutor/writing instructor for 826DC. He lives in Arlington, VA. Author Photo by Matthew Bailey

WWPH WRITES FICTION

History Lesson

by Peter Philipps

She was my first love. I was eight. She was my teacher. And under normal conditions, that would be all there is to tell. But normalcy was a thing of the past, and what would have been a third grader’s harmless crush on his teacher took on a life of its own.

It all began one fateful day after my family had fled Germany for the assumed safety of Czechoslovakia, only to stand at our living room window and watch Nazi troops march into Prague. Now it was the turn of the Jews of Czechoslovakia to be pushed to the fringes of society, including students like me who were expelled from public school and forced to attend all-Jewish schools. “We went in the wrong direction,” was my father’s first reaction.

Even before I got used to my new schoolmates and the new curriculum, I climbed onto my front-row desk one day and threw my arms around my new teacher, the prettiest in Prague’s Jewish school. Another teacher would probably have scolded me or sent me to the principal, but Miss Berger simply guided me back into my seat and continued with the lesson.

A few days later, I did it again, only this time I planted a kiss on Miss Berger’s cheek. Once the titters of the class died down, she asked me to stay after school.

“Is anything wrong?” she asked, perching on the edge of my desk.

I couldn’t confess my love, or tell her that her perfume lingered in my nostrils long after the school day ended, or that I disliked having to share her with sixteen other boys and girls. But I finally found my tongue long enough to promise not to misbehave again. I was about to start for the door when

Miss Berger stopped me and said, “Please go back to your desk, Albert.”

Confused, I did as I was told and watched her write something on a sheet of paper. She then handed it to me in a sealed envelope and said, “Please give this to your parents.”

I walked home in dread, fully expecting a dressing down. But instead of summoning my parents to school, as I had feared, Miss Berger wanted to make a home visit.

The day she came, I didn’t have to be told to go to my room. I kept my ear pressed to the door but couldn’t make out a word of what was being said. After what felt like an endless wait, my mother opened the door. “Miss Berger is staying for coffee,” she said. I could hardly believe my ears.

Once we were seated around the kitchen table, it took my mother almost no time to ferret out that Miss Berger was single and, like us, desperate to emigrate. “Then you must come for dinner every Friday night,” my mother said with a hand on Miss Berger’s shoulder. She sighed, then added, “As long as we are all still in Prague.”

“We are not religious,” my father explained, “but we light the Sabbath candles and enjoy a little glass of wine.” He leaned his head close to Miss Berger for a moment and said, “I see you play the violin.”

“You can’t miss it,” she said, reddening and touching the telltale mark under her chin. “Do you also play the violin, Mr. Levy?” she asked.

“No. The piano. Perhaps next Friday you will bring your violin and we can play some duets.”

“I would like that very much,” Miss Berger replied.

“Ja, then we will play a little Mozart and a little Beethoven—”

“I am a mere amateur,” she broke in.

“So am I,” said my father, and they shared a brief laugh.

That Friday, Miss Berger arrived holding her violin in one hand and a box of chocolates in the other. After dinner, she and my father played a Beethoven duet. I listened in reverential silence. It didn’t take long before I began to clamor for violin lessons.

But it was not to be. On the last Friday of April, Miss Berger informed us that she was getting married. I felt the ground shift under my feet. “His name is Jan,” she said, “and he is a ski instructor.”

“I would like both of you to come for dinner one night next week,” my mother said elatedly, “so we can meet this lucky young man of yours.”

Miss Berger accepted with alacrity and two days later brought her fiancé to our house for dinner. They arrived bearing a huge bouquet of flowers. Jan patted me on the head and paid no further attention to me. While we were eating, I had an almost uncontrollable urge to shove my fork into his belly.

By the time we finished dessert, Miss Berger and my parents agreed to have the wedding in our apartment. “The sooner the better,” my father said.

“Our days here are numbered.”

The brief civil ceremony took place in front of a few old friends and two of Miss Berger’s colleagues. I cried throughout the ceremony. When it was over, Miss Berger, the name by which I will always remember her, dried my tears and enfolded me in a huge hug.

The following day, I accompanied my parents to the railway station to see Miss Berger and Jan off on their honeymoon, their destination a secret. As Miss Berger was about to board the train, I fastened my arms around her waist and tried to hold her back. “Albert, Miss Berger will be back at school next week,” my mother assured me.

But a week felt like an eternity—and so it turned out. A few weeks later, we also managed to leave Prague—and none too soon, as rapidly evolving events would prove. Weeks, months, and then years passed without a word from Miss Berger. Yet I still have a fading hope that one day, somewhere, we will meet again.

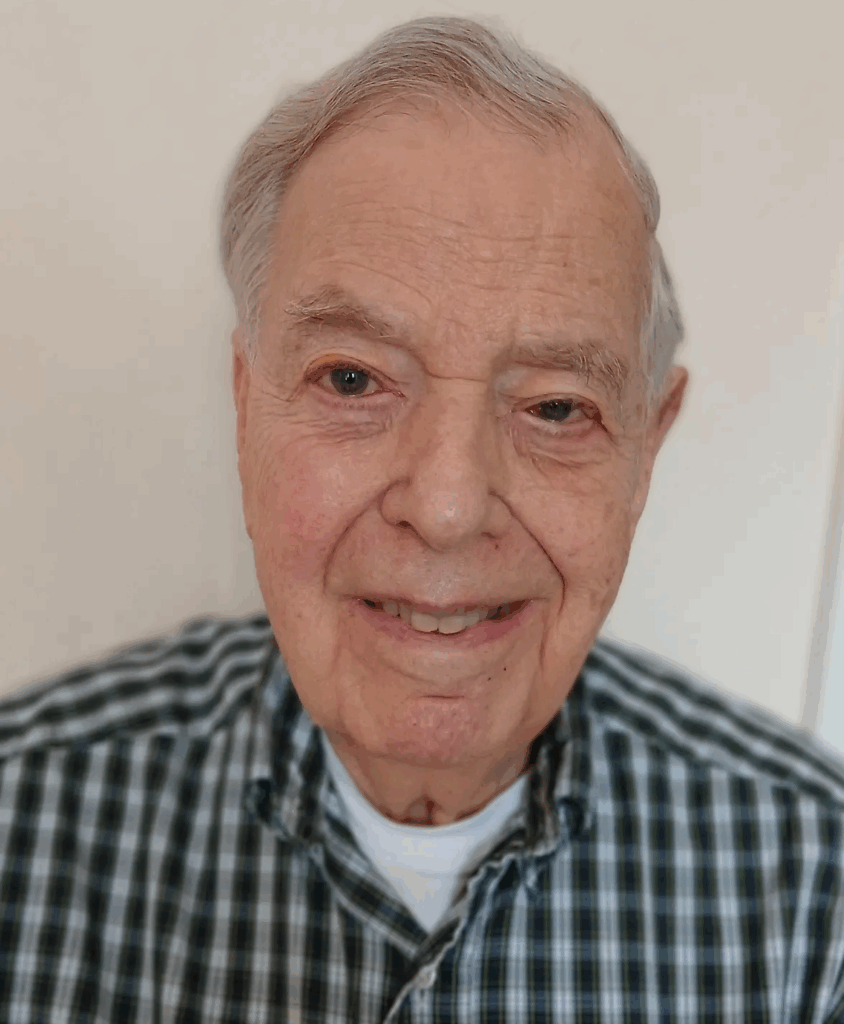

Peter Philipps, a survivor of Nazi Germany, is an award-winning former staff writer and editor of The New York Times and Business Week, among other publications. His fiction has appeared in SLO-WORD, Jewish Fiction, and the Arlington Literary Journal. He lives in Bethesda, Maryland.

The Biggest Fan

by Eben Atreyu Bracy

Everything has a home. Mine was the dirt at Cleveland Stadium, where I’d been since 1932, but that all changed the night we met in 1974. When you pulled me out of the dirt that I’d known for so long, no one asked any questions. There were no search parties. The game, as it always does, went on. Meanwhile, you took me home, put me in a glass case and hung me up on your mantle. Flanked by twin Rusty Torres bobble heads, I’ve become nothing more than an altar piece. There’s no grass here, no spikes to slide across my surface, nothing but you and the items you’ve surrounded yourself with. Maybe for you, my life isn’t really a life at all, but a consequence of the game you’ve put so much meaning into.

Although you have been to the stadium more times than you can count. It will never be your home like it was for me. For decades, I was entrenched by it, held by the red earth that you think nothing of. You don’t think of it as a part of the stadium, because, like always, you center the game on yourself. Really, it is more of the game than you know, but there is no way for you to know the stadium. You’ve never seen it empty. You haven’t seen the field stretching ahead of you, the mound rising over you like a sun that never sets.

Where you’ve seen it, is from afar. In those empty seats that in winter, take on the shape of a mouth, anxious for the next season. That’s what separates you from the players, it always has. It’s also why I’ve preferred practices to games. During practices, the antagonism between pitcher and batter evaporates. Trapped on his lonely island, the ball becomes the pitcher’s only way to know the wider world behind him. The batter, unable to leave his box, can only do so with the connection of the ball. Freedom lies alone in their knowing each other, in the brief intimacy of their union. That moment is the truth of the game; the players know it deeper than you ever could.

But then again, you know the game, don’t you? You’ve watched it since you were a kid, you know the rules better than any ump on the field. You often think about becoming one, I mean, the game’s better in your hands, right? The language of the game was mine before anyone’s. Strike. Ball. Out. Safe. These were my first words. You know them as signs pointing towards defeat or victory. To me, they explain your world. A strike is never just a whiff. A strike, more than anything, is the failure of interconnection. Not just between the batter and pitcher but all people everywhere. When a strike is thrown, the pitcher is trying to remain on his island because it’s all he knows.

From the mound, he can see others, but he cannot reach them, to do so would invite death. The pitcher, his arm snapping as he throws a strike, pushes against all connection. Despite the pitcher’s own wishes to leave his island, his victory requires his loneliness. That’s where the frustration comes from. It’s never that the batter missed his swing, it’s that deep down you want them to have connection. You’ll say this failure is what drives the pitcher and his side to victory, that victory is what everyone wants. You’ll tell me no one wants to lose, and that’s why he throws strikes. That he’s not lonely. He just wants to win like you. Like every other player, he wants what you want. Being the sort of fan that you are, you know them all: legends, benchwarmers and everything in between. Alive or dead. In exchange for your soul, your mind has become an apocrypha of the game. One that tells you that you know the players, that you understand their world.

You know that the world, outside the game, has left you. Deep down it hurts. That’s why every loss is a raging fire across your body. Why every strike digs deep inside of you and won’t let go. That’s why you rushed the field in seventy-four, the first to leap over the stands, as a horde thundered behind you, summoned by your bottomless rage. That night, you ripped me up from the field. That night you stole home.

Eben Atreyu Bracy was born in Flint, Michigan. His work has been published in The Twin Bill, Lucky Jefferson, and Constellate. He is a two-time winner of Old Dominion University’s Jerri Dickseski Fiction Prize.

WWPH NEWS

AMERICA’S FUTURE…be the first to read. Now available for everywhere books/ebooks are sold. AMAZON. BOOKSHOP. BARNES & NOBLE. or maximize your support here at WWPH DIRECT.

JOIN BLACK WOMEN WRITERS published in AMERICA’S FUTURE for a bold LITERARY SALON. RSVP, please, here.

OUR LAST LITERARY SALON OF 2025! DON’T MISS!

WWPH Writes is now open for submissions! We are reading for 2026, including poetry, flash fiction, and creative nonfiction (1,000 words or less). We are looking for your authentic voice; lines that thrill and surprise us; poetry and stories from writers across DC, Maryland and Virginia. We are a paying market: $25.00 to you, with our hope that you pay it forward and buy a book from a small press. And, we are free to submit to! More details on our Submittable site here.

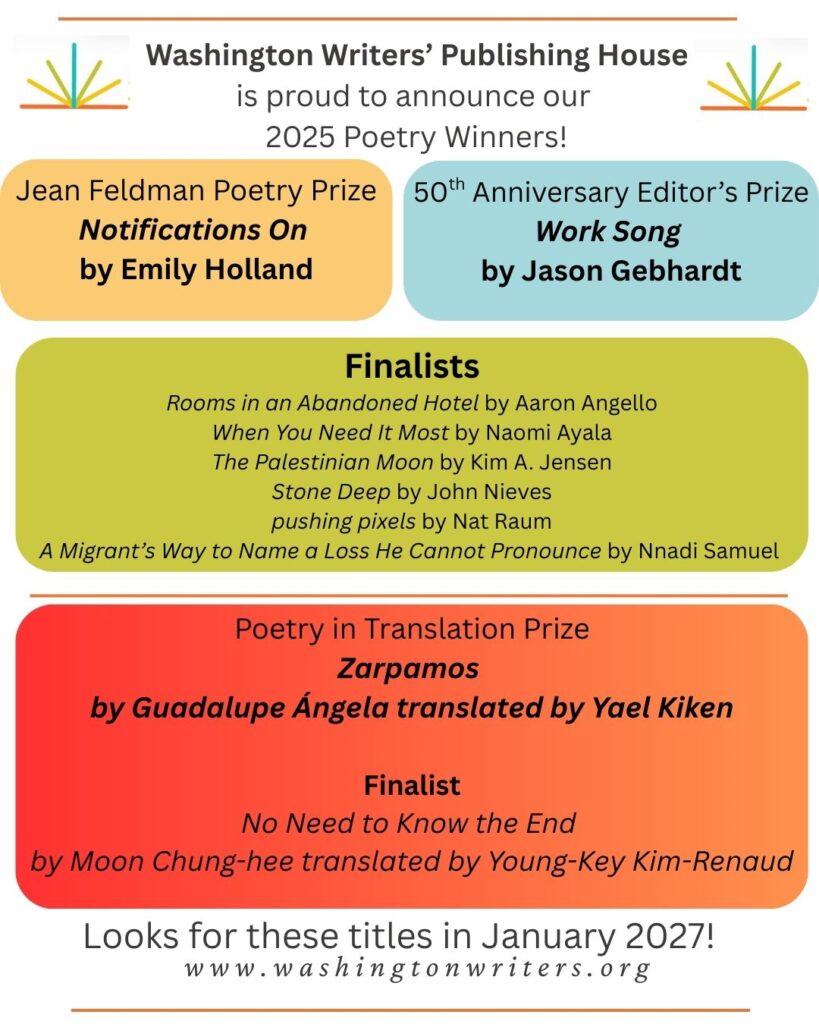

2025 Poetry Prize Winners! Each receives $1,500, publication, and editorial and promotional support. MORE ON THESE AWARD-WINNING POETS AND THEIR BOOKS HERE. Thank you to all who submitted! The fiction winner and finalists will be announced on or about November 1st. For those planners in the community: We will be opening our manuscript contests in fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction (memoir or essay) in late spring. Keep reading WWPH Writes for details.

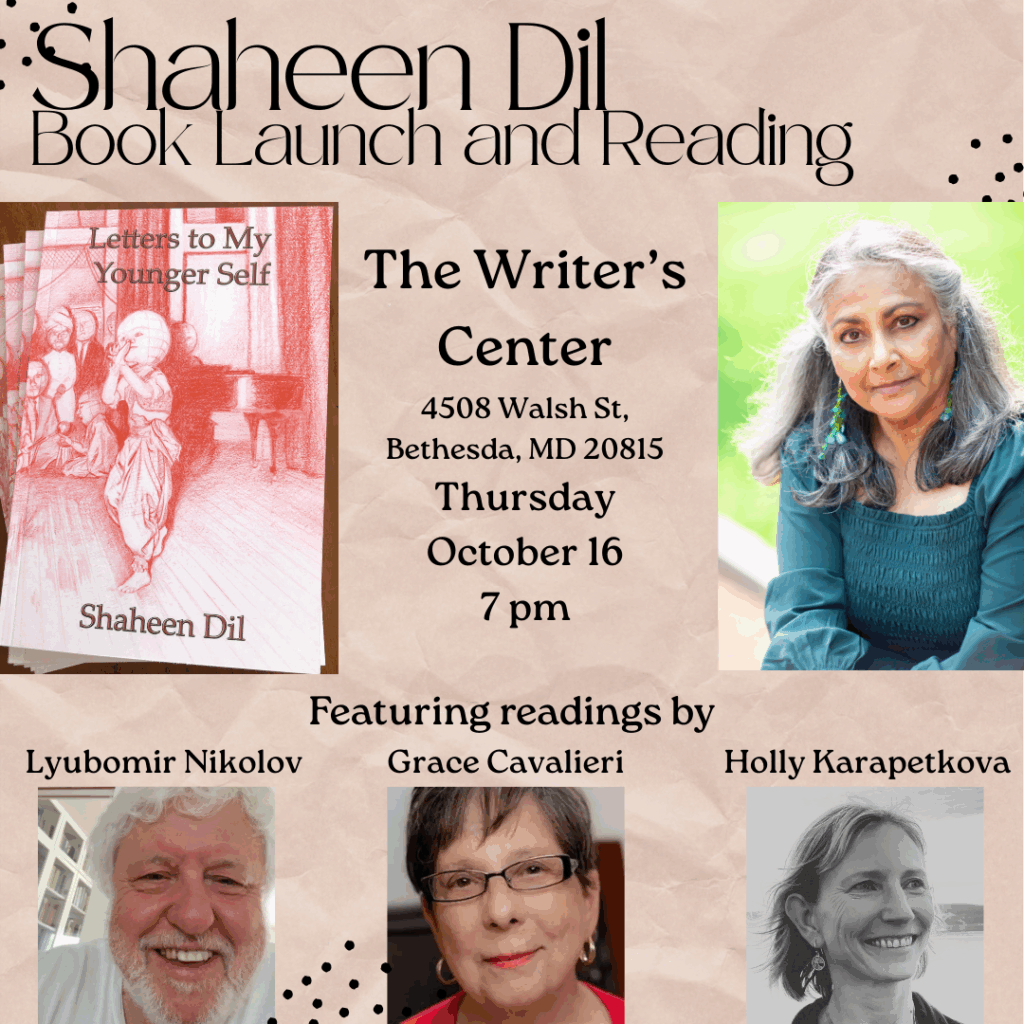

From our wonderful community… a must-attend reading this Thursday, October 16 at the Writer’s Center of Bethesda