News & Events

2024 Manuscript Winners

in Fiction, Poetry, and Nonfiction

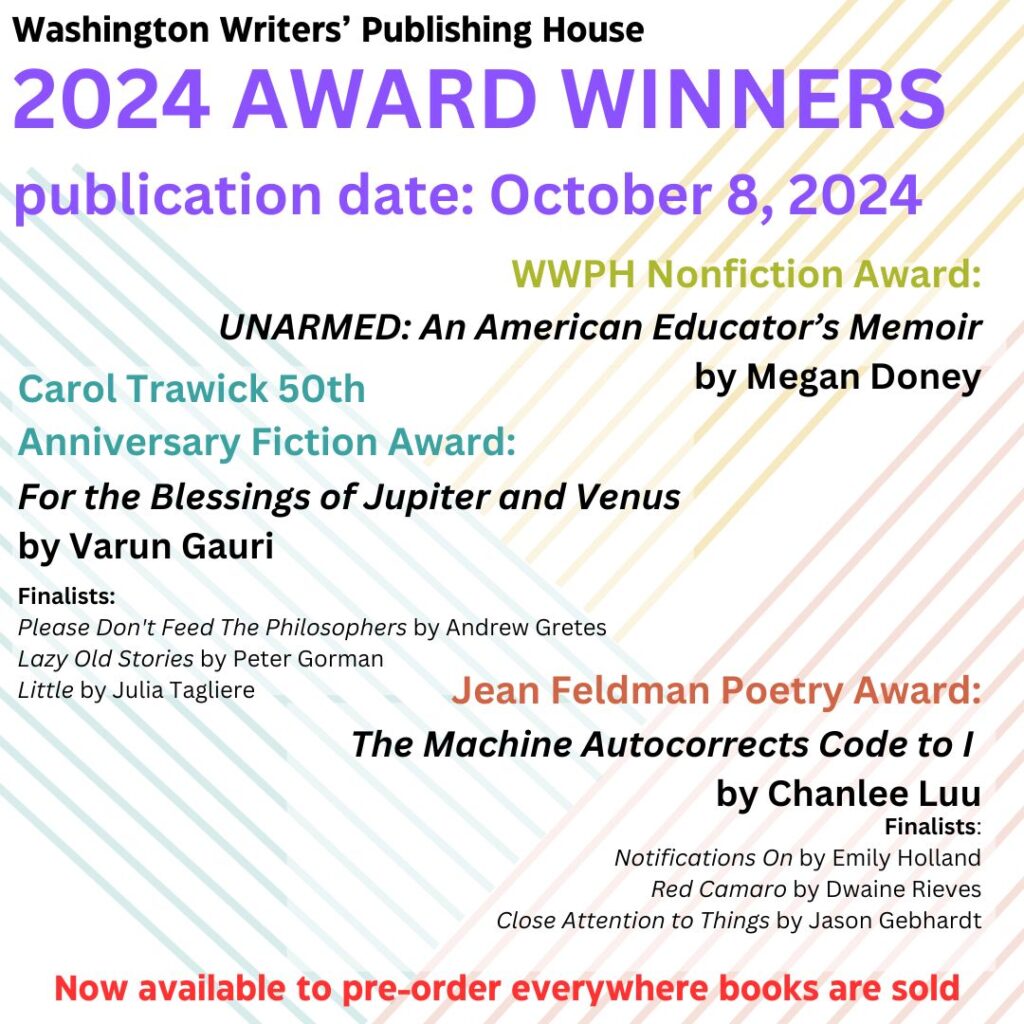

Award-winning books will be published on October 8, 2024

Tuesday, February 13, 2024 – The Washington Writers’ Publishing House is pleased to announce the 2024 winners of its annual fiction, poetry, and nonfiction manuscript contest. Varun Gauri of Bethesda, Maryland, will receive the Carol Trawick 50th Anniversary Fiction award for his novel For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus. Chanlee Luu of Roanoke, Virginia, will receive the Jean Feldman Poetry Award for The Machine Autocorrects Code to I. Megan Doney of Christiansburg, Virginia, will receive the Washington Writers’ Publishing House Nonfiction award for her memoir UNARMED: An American Educator’s Memoir. The first prize in fiction will be $2,000. First prizes in poetry and nonfiction receive $1,500. All books will be published by The Washington Writers’ House on October 8, 2024, and receive editorial and launch support.

Finalists for the Carol Trawick 50th Anniversary Fiction Award include Please Don’t Feed the Philosophers by Andrew Gretes, Lazy Old Stories by Peter Gorman, and Little by Julia Tagliere. Semi-finalists include The Great Grownup Game of Make Believe by Lauren Woods, Little Catastrophes, Ordinary Joy by Morgan Kovacs, and Gaslit by Amy Freeman.

The finalists for the Jean Feldman Poetry Award include Notifications On by Emily Holland, Red Camaro by Dwaine Rieves, and Close Attention to Things by Jason Gebhardt. Semi-finalists include Eye Shine in the Dark by Kristin Davis, Night Westerly by Rebecca Lilly, Late-Stage Capitalism is the Story of Sisyphus, but America’s The Hill and His Soul’s The Boulder by Sean Murphy.

The manuscript contests are judged by members of WWPH, all of whom consist of past winners. All manuscripts are considered blind.

Learn More About Our 2024 Winners:

Varun Gauri’s short fiction was nominated for a Pushcart Prize and recognized in Best American Nonrequired Reading. His novel, For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus, is a love story and comedy of manners about a young couple who, despite having dated, choose an arranged marriage. He teaches courses on behavioral economics and global poverty at Princeton University and lives with his family in Bethesda, Maryland.

Chanlee Luu is a Vietnamese-Chinese American writer from Virginia. She received her MFA in creative writing from Hollins University and BS in chemical engineering from UVA, where she competed in poetry slams. She writes about identity, pop culture, science, politics, and everything in between. She can be found on Twitter @ChanleeLuu, and her work in Snowflake Magazine, the gamut mag, Cutbow Quarterly, Tint Journal, Honey Lit, The Offing, and diaCRITICS, among others, all at chanleeluu.weebly.com.

Megan Doney is a writer and English professor in Virginia. Her work has been published in Ilanot Review, New Limestone Review, Rappahannock Review, Creative Nonfiction, Earth &;

Altar, and Inside Higher Ed, as well as in the anthologies Allegheny and If I Don’t Make It, I Love You: Survivors in the Aftermath of School Shootings. Her essay “The Wolf and the Dog” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She was a Fulbright scholar in South Africa in 2007, and returned there in 2015 to study reconciliation and violence. Doney earned an MFA from Lesley University.

Washington Writers’ Publishing House is a non-profit, cooperative literary organization that has published over 100 volumes of poetry since 1975, as well as fiction and nonfiction. The press sponsors three annual competitions for writers living in DC, Maryland, and Virginia, and the winners of each category (one each in poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction) comprise our annual slate. In 2021, WWPH launched an online literary journal, WWPH WRITES, to expand our mission to further the creative work of writers in our region. In 2024, WWPH launched our biennial works in translation series. Learn more about our literary cooperative nonprofit press, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary.

WASHINGTON WRITERS’ PUBLISHING HOUSE TO PUBLISH WORKS IN TRANSLATION BEGINNING IN 2024

October 27, 2023 –The Washington Writers’ Publishing House will publish their first-ever translation with Aguas/Waters by Miguel Avero, translated by Jona Colson on May 16, 2024, representing a major expansion of the regional press’s mission to include works in translation from cultures/languages that have significant representation in the Washington DC, Maryland, and Virginia area. The Washington Writers’ Publishing House has committed to publishing a biennial translation collection from a DMV translator going forward—global writers translated by our regional translators.

“Miguel Avero’s poems demonstrate linguistic experimentation and music, which is infused in both the original and the translation. Aguas/Waters by Avero helps make sense of life and the self, highlighting the tradition of magical realism, and this translation will bring this important author to readers in the DMV and in the nation,” notes Jona Colson, author ofSaid Through Glass and co-president of the Washington Writers’ Publishing House. Partial funding from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities has made this project possible.

Miguel Avero, author of Aguas/Waters, is a prolific contemporary writer in Uruguay. Uruguay is the smallest Spanish-speaking country in South America and is often overlooked for its literary significance. Uruguayan poetry is difficult to find in translation, and his work carries themes that include his love for his motherland, civil war, and political corruption. Avero’s poems elevate impressions of the everyday into something that we can only know through language and image.

Miguel Avero, born in Montevideo, Uruguay in 1984l, is a poet, narrator, essayist, teacher, and researcher. Co-founder of Orientacion Poesia and On the Path of Dogs. He directs the writing workshop “Puerta Quimera.” Avero Participates in various national and international anthologies. He has published the collection of poems, including Arca de aserrin (Ediciones en blanco; 2011; republished in 2021 by Ediciones del Demiurgo), the nouvelle Michaela Moon (Travesia Ediciones, 2014; republished in 2015.) In 2016, Avero published the books Let Nobody Ask About You (Bestial Barracuda Babilonica, poetic prose) and La Pieza (Walkie Talkie Ediciones, poetry). He won the first Espacio Mixtura poetry prize with the book Libreta insomne (Editorial Primero de Mayo, 2019). In 2020, he published Haiku mate (Ediciones del Demiurgo, poetry) co-authored with the Minuan Poet Leonardo de Leon. In 2022, Prosperidad, a hybrid text of poetry, essays, and memoirs, was released by Ginko Ediroia. Recently, by the same publishing house, the book of short stories Michaela Moon y otros tentativas (2023) was published. Part of Avero’s work has been translated into English and French.

Jona Colson is an educator and poet. He graduated from Goucher College with a double Bachelor’s degree in English and Spanish and earned his MFA from American University and a Master’s in Literature/Linguistics from George Mason University. His poems have appeared in The Southern Review, Ploughshares, The Massachusetts Review, and elsewhere. In addition to writing his own poetry, he also translates the Spanish language poetry of Miguel Avero from Montevideo, Uruguay. His translations can be found in Prairie Schooner, Tupelo Quarterly, and Palabras Errantes. He is currently a professor at Montgomery College in Maryland where he teaches English as a Second Language. He lives in the Dupont Circle area of Washington, DC.

AGUAS

Agua en la mañana alquitranada

o en la noche que cubre

de cartones el amanecer.

Agua en los tejados anidando.

WATERS

Water in the tar-dark morning

or at night where the cardboard boxes

block the sunrise.

Water nesting on rooftops.

Aguas/Waters

Poetry

By Miguel Avero (translated by Jona Colson)

Washington Writers’ Publishing House

On Sale: May 16, 2024

ISBN: 978-1-941551-39-4

Washington Writers’ Publishing House is a non-profit (501c3), cooperative literary press in continuous operation since 1975. The press sponsors three annual competitions for writers living in DC, Maryland, and Virginia. The winners of each category (one in poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction) comprise our annual slate. In 2021, WWPH launched an online literary journal, WWPH WRITES, to expand our mission to further the creative work of new and established writers in our region. The press will celebrate its 50th anniversary year in 2025.

.