WWPH INTERVIEWS DORIAN ELIZABETH KNAPP

Dorian Elizabeth Knapp is the author of Causa Sui (2025), winner of the Three Mile Harbor Press Poetry Prize, Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak (2019), winner of the Jean Feldman Poetry Prize, and The Spite House (2011), winner of the De Novo Poetry Prize. She is the founding director of the Low-Residency MFA in Creative Writing at Hood College and lives in Maryland with her family.

The CAUSA SUI Interview

by

Eric Julian Baker

Palimpsest and found poems dot your latest collection—what and who has inspired you to employ these forms throughout Causa Sui?

Nicole Sealey’s The Ferguson Report: An Erasure (2023) was the inspiration for “‘We the People’: Found Poems from Project 2025.” I started that sequence as an erasure, but erasing 900+ pages of text quickly became overwhelming, so I wrote them as found poems instead. Sometimes I would pick up words and phrases from a single page, and sometimes I would start with a single word or phrase and then build the poem around it. Once I finished a poem, I would check to make sure the words I used were also included in the text of Project 2025.

The ChatGPT erasures/palimpsest poems originated from playing around with ChatGPT. The first one I wrote was “Poem in the Manner of a ChatGPT Artist’s Statement.” Writing that one made me realize that I could have some fun exploiting AI’s limitations, so I started giving ChatGPT various prompts—“Write the lyrics to a pop song about the myth of Persephone,” etc.—and then created erasures from them. Originally, I crossed out the ChatGPT text and bolded and italicized the words I chose, but then I decided I wanted the ChatGPT text to be readable, so I grayed it out, creating what you call “palimpsests.”

Thinking of your interest in Nicole Sealey’s own documentary and erasure work, I was curious whether or not you felt writing your found poems had required you to read more closely, and if you’d be willing to tell us a little about that experience?

Yes, writing “‘We the People: Found Poems from Project 2025” forced me to read Project 2025 closely, which was a chilling experience. I was struck by its comprehensiveness and how it aimed to address every aspect of American life, from social issues to the natural world. Because it’s so long, it uses a lot of words, and strange ones too, ones you wouldn’t expect to find in a political tract, such as “creatureliness.”

In a time that increasingly seems to promote LLM-based art and writing, you raise an important and exigent concern in Causa Sui, asking “Is Poetry Dead?” What do you think it will take to keep poetry alive?

The title of that poem is poking fun of articles proclaiming the death of poetry that appear every few years in magazines like Harper’s or The New Yorker. I don’t think poetry is dead or in danger of going extinct, but I am alarmed by how little poetry is currently being taught, and I do wish we lived in a country where poetry was part of the national consciousness and culture, as it is in other countries. After having experimented at length with ChatGPT, I don’t think we have anything to fear in terms of AI surpassing human capabilities when it comes to writing a poem, at least not yet.

From Britney Spears and Talking Heads, to rewriting the story of Persephone as a modern day anthem—pop music appears throughout Causa Sui. What inspired you to weave your love of pop into your writing for this collection?

This book has fewer references to pop culture and music than my second collection, Requiem with an Amulet in Its Beak, does, which contains numerous appearances by Kurt Cobain, David Bowie, and Prince. The only musicians that appear in Causa Sui are Britney Spears, Talking Heads, and Dolly Parton, and each only once. American culture is one of my primary subjects, and since pop music is a large part of American culture, musical artists appear a lot in my work.

Who are your top three artists this month?

One of my favorite contemporary novelists is R. F. Kuang. I’m reading her new novel, Katabasis, right now. Richard Siken is a favorite contemporary poet with a new collection, I Do Know Some Things. In terms of visual art, I’ve recently been introduced to Yin Xiuzhen, a contemporary Chinese sculptor and installation artist whose work I find fascinating.

In the titular poem of your collection, you reference Ernest Becker, writing: “…all human activity revolves / around the subconscious attempt to deny / the reality of our own mortality,” which echoes the Hopkins quote you open Causa Sui with. If you could pick one poem of yours to be remembered for, is there one you would choose?

I think the most significant poem from this collection is “‘We the People’: Found Poems from 2025” in terms of being a record of this moment in history. A century from now, what would a reader think about that poem and what it says about this moment in history? How will this moment be written and remembered? These are questions I ask myself all the time.

WWPH INTERVIEWS MICHAEL GUSHUE and KIM ROBERTS

AT THE END OF THE WORLD WITH KIM ROBERTS AND MICHAEL GUSHUE

THE WWPH INTERVIEW

By Demitra Moutoudis

Q&A for the End of the World (WordTech, 2025) is a collection of poems from Kim Roberts and Michael Gushue. The collection was inspired by weekly movie nights that the two authors had where they would watch sci-fi films together. Q&A’s structure is a call-and-response, where Robert’s poems pose “questions” about each of the movies while Gushue provides “answers.”

DM: What was the moment that really set this project in motion?

Kim: My fiancé, Tracy, saw that the Smithsonian Sackler Museum was showing a free matinee of Mothra versus Godzilla, and she got us tickets. I’d never seen any of the Godzilla movies, and she immediately suggested that we get an extra ticket for Michael, who is an aficionado, someone obsessed with these movies. We came out of the theater, and I was just flabbergasted by this movie.

I had heard about Godzilla movies, but I kept peppering Michael with questions about how un-sciencey the science fiction was. Michael was like, “You’re missing the point.” I went home, and I immediately wrote a poem called “I Have So Many Questions After Watching Mothra vs. Godzilla.”

We’ve been in a writer’s group together for a long time, so I brought it to the writer’s group. Then, Michael went home immediately and wrote the answer, “I Have The Answers to Mothra vs. Godzilla.” We know each other’s work really well, and because Michael thought my questions were so absurd, he decided I needed an education.

DM: Where did your inspiration to collaborate on this project come from?

Kim: Michael invited me to start going every Wednesday afternoon to his house because he owns all of these movies.

Michael: It was every single week for 9-10 weeks. Normally, I’m a slow writer, but having to respond to Kim’s poems so quickly was a prompt that I don’t normally have.

We decided on a theme, which was the “end of the world.” We divided the theme into three categories: something giant stomps us to death, something giant crashes into us and kills us, or we blow ourselves up.

DM: How did you decide on which movies to watch?

Kim: Michael picked movies that he thought were essential to my education, but as extra added value in the book, we included a list of additional movies that we did not get to watch.

Michael: And we had great fun watching them. I would try to avoid extensive lecturing and would just give a brief summary. Then, Kim would go off and write a poem, and then I would try and catch up with her. My “answers” are probably not completely accurate and are more of a response.

DM: If you were to pick a new-release film to add to the poem collection, what would you pick and why, if anything at all?

Michael: Maybe I would pick Arrival. But genres have become so entangled with each other that a lot of science fiction is really more like horror. They’re more fun to watch. I think you could have plenty of questions about that movie.

Kim: I would want to argue for, although it’s not that recent, 12 Monkeys. La Jetée is the last movie in the book that we wrote a pair of poems about, and it’s an adaptation. So is 12 Monkeys, and it’s really fun to re-watch that movie after watching it. The thing about the original movies is that since they’re all set in the 50s and 60s, we forget how much racism and sexism were just sort of taken for granted. I think there’s no way not to see them with nuance.

DM: Do you think if you were to write this book based on modern sci-fi movies, that your general sentiments and thoughts would remain the same?

Kim: You would have to say yes, not only because we’re in a different place in terms of fear of nuclear annihilation, but also just the special effects. I mean, talk about how movies have changed.

Michael: I think science fiction movies tend to reflect the anxieties and concerns of the times. Our concerns are different now. But also, I think there’s a real purity to the 1950s science fiction movies where sci-fi was a new genre, and they were creating stuff for the first time. Movie genres have been smashed together so often in order to attract wider audiences to the point that sci-fi is almost not even the same thing. Q&A For The End of The World would be a very, very different project today.

DM: Which of the films’ directors would you most want to sit down with and have a conversation with? Would you ask Kim’s question-poems, talk about Michael’s answer-poems, or have a conversation about them both?

Kim: I have questions for the director of the Godzilla movies (Ishiro Honda).

Michael: I’d certainly want to ask Honda about the complexities of putting it [Godzilla] together. Honda has done other things besides Godzilla films, but it would be interesting to hear what he has to say about the studio system, and how he negotiated through the studios to get those made too. There’s also the whole Godzilla evolution, where Godzilla is a villain through Mothra vs. Godzilla, and then he becomes the hero of Japanese culture, where he’s defending Japan from things like smog monsters, which represents everything bad that comes out of America.

DM: “I Have No Answers to La Jetee,” clearly the movie was very avant garde and quite an inspiration to films following its release. Interestingly enough, Michael, it feels like you do give an answer to the film and its subject matter like you do have an understanding, but at the end you say you don’t know what it means.

So then, why in particular was this the poem you found yourself having “no answers” to, despite having a lot to say?

Michael: The film itself is inexhaustible. Its themes are entangled with many of my obsessions: the themes of time, memory, the substance of the past and the substance of the future, things like that. Even though I have seen it a bunch of times, I still find it mysterious. There’s something inexplicable about the end, as there is with all moments of beauty.

What’s compelling is, “what do they [themes] evoke inside us?” is a question I really don’t have an answer to. Even though it might seem like a satisfactory poem to read, I don’t really feel like I know the film yet.

Kim: It’s the one movie in all of the group that resists narrative the most. You can’t understand the beginning until you’ve seen the end.

DM: Kim, this next one is for you. “I Have So Many Questions.” This piece feels like the wrap-up of the continual conversation between you and Michael. The poem has a sense of finality not only to the conversation, but to the discussions of reappearing themes and subject matters in sci-fi films (the portrayal of women, frequent religious undertones, questioning the morality of humanity, nuclear annihilation, etc.).

Kim: How did it feel to end the conversation? Do you think it’s best that some questions go unanswered? I think that what these types of movies do is reflect American culture. But also, it was a way for me to actually learn more about Michael. We’ve been close friends for a very long time, and it was a different sort of understanding. This obsession of his goes back to childhood, so in a way, it was like investigating his childhood again with him. There’s that personal part of how these movies affected me because they were seen with Michael.

Then there’s also sort of that larger conversation about the purpose of pop culture, the purpose of these kinds of cultural touchstones for serving as a mirror of the larger cultural obsessions, and the imagery that we sort of get imprinted with and how that affects us, how that affects our identity as Americans. I just think that with these movies, there’s something that is worth examining further. And Michael was right. I needed an education in this.

DM: Do you think you’ve fully come to embrace that? Do you think by the end of when you wrote Q&A For The End of The World, that “I Have So Many Questions” embodies that feeling?

Kim Yes. My skepticism remains, but I do have a greater appreciation for science fiction.

DM: What movie are you both looking forward to seeing next? Will you stick with watching sci-fi movies or switch to another genre?

Michael: This has been an ongoing discussion between Kim and I’ve offered to switch genres, but that’s an open question. As far as our projects go, I’ll go see anything.

DM: Is there anything else you want to say about this collection now?

Kim: I made up a form for the poems themselves that helped sort of propel them forward for me. So, you will notice that there’s repeating end-words. Each poem is written in couplets. The end word of the second line becomes the end word of the next stanza’s first line, and then I repeat the first line in its entirety as the last line. Having that form gave me a shapeliness for putting these together. I tend to write more in forms than Michael does. Michael’s free verse ended up being, for the most part, in couplets, because I had started that way, but we decided it was okay for the questions to be formally different than the answers as well. So, I think that the poems still remain distinct. They reflect our personalities.

Michael: The whole project from the beginning was a lot of fun. I was amazed at how quickly it went, how quickly it got picked up and into the public eye. I also had so much fun writing the notes, which are a little bit eccentric. I just try to pick the weirdest stuff about each movie and say it. And I had a great deal of fun, so I hope people don’t bypass that either.

DM: The element of collaboration is very central to Q&A. In what way does the collection speak for the art that collaborative efforts can produce?

Kim: Both of us have written books in collaboration with others before, and I don’t know that a lot of poets are doing these kinds of collaborations. But both of us are drawn to it.

Michael: If you’d asked me ten years ago, I would have said, “I don’t even understand how something like poetry can be collaborative, since it’s so personal.”

Kim: I never would have thought I’d be doing back-to-back collaborative things. For me, a lot of that is a direct consequence of the pandemic, and wanting to feel like I just wanted to connect more with other artists whose work I admired, and collaboration is one way to do that.

Working with someone else sort of pulls you out of yourself, and you end up doing stuff that you normally wouldn’t.

Michael: You can’t underestimate community and collaboration, and those kinds of things that link us together. It’s so important.

Now available everywhere books are sold including here at bookshop.org.

This interview was a project by the Washington Writers’ Publishing House’s 2024-2025 Fellow, Demitra Moutoudis. She is a recent graduate of American University with a degree in Public Relations & Strategic Communications and a minor in Creative Writing. Much gratitude to Demitra Moutoudis for her work with WWPH.

WWPH INTERVIEWS: Dr. Tonee Mae Moll on her new edition of You Cannot Save Here

Dr. Tonee Mae Moll is a queer and trans writer and educator. Her debut memoir, Out of Step, won the 2018 Lambda Literary Award and was featured that year on the American Library Association’s annual list of notable LGBTQ+ books. Tonee Mae’s poetry has also received the Adele V. Holden award for creative excellence and the Bill Knott Poetry Prize. She is, most notably, a Gemini. More about Tonee Mae here.

You Cannot Save Here won the Jean Feldman Poetry Award from the Washington Writers’ Publishing House.

Available everywhere books are sold. However, support your WWPH and purchase your copy here.

Can you tell me about the significance of You Cannot Save Here in your writing career and the importance of its newly reissued edition?

It’s exciting because it’s my first full collection of poems. So, my first full book was a memoir, but You Cannot Save Here was the book that helped establish, hey, I’m a poet, and I have a book of poems, and it won an award, and I know what I’m doing. It’s a creative portion of my PhD dissertation, so it’ll always have a special place there too. And then the re-release is huge. It’s hard to be a writer, and people would say, oh, I want to read your work, and then be like, oh, well, here are two books with someone else’s name on it that you should go read, but I promise that was, or at least used to be, me. So having my books with my name on it is huge for that reason. I can point to them and not feel weird about pointing to a dead name or pointing to a photo on the back cover that doesn’t look anything like me anymore.

What is a word or words that you think best encapsulates the feeling of your poems throughout You Cannot Save Here?

It is apocalyptic, so that’d be the first word. I’ve had friends who described it as hope punk, and I love that reading of it. But a friend and collaborator of mine, Tracy Dimond, called the work posy-goth, which we discussd is like, sort of epicurean. The world is ending, and the world is bad, and there’s no lying about that. But it’s also like, here’s what we can do despite that. That’s build together, that’s enjoy life, that’s pursue happiness and pleasure.

Several years after completing the book, how do you reflect on your poetry and who you were as a writer during that time?

You know, it’s interesting because it’s as much me and having transitioned as it is the world and how it’s changed, right? So, the book started with an obsession about climate disaster, but from starting writing to it being published, we also elected the 45th president. We also have the global pandemic. All these other disasters happened and have continued to happen. And so, in the years since I started writing, in the years since You Cannot Save Here first dropped, the world has changed. And then, of course, I’ve changed too. And so, what you’ll see in the book are some poems that reflect on gender dysphoria from someone who is really yet to fully figure it out. And lately, it’s from someone who knows she’s a woman and also is undergoing the painful, contentious process of medical transition. Then on top of that, I’ve experienced a divorce since then, and so I’m also just writing sad girl falling in and out of love poems, and a lot has changed, both with me and the world around me.

Has your inspiration and writing changed since you transitioned?

I think so. I think I’m more comfortable occupying this particular voice and particular inspirations. I think prior to transition, I had, and I probably should not have had, but I did have an anxiety about saying all my like inspirations are these 20th century feminist poets and feminist theorist folks, and I just like, I shouldn’t have done that, right? Like people who think their boys are allowed to cherish feminist writers and feminist thinkers, too. But I’m much less self-conscious about that now and acknowledging my influences and writing poems that reflect that too.

Why do you think people should read these poems and buy this collection right now?

Well, number one, I would like for people to just have my book. More specifically, I would like them to have my name on their shelf. The new edition is for that reason, but the poems themselves continue to be relevant. The poems continue to be relevant. We continue to live in them more than ever. I’m feeling the same energy I felt when I wrote this book, which is like, wow, these are disastrous times. These are devastating times. How am I supposed to go to work? How am I supposed to go on dates? How am I supposed to deal with the oncoming of spring, when my news feed looks the way it does? You know, when we’re worried about the lives of ourselves, our neighbors, and our comrades overseas, how am I supposed to just get on with life when things look the way they do? That is how I felt when I started the book. Thinking about climate disaster, how I felt about the election of the 45th president, how I felt about COVID when it hit us, how we just keep going? How do we find joy when the world looks the way it does, that in 2025 continues to feel relevant, maybe even more than it did then.

Do you have any advice for aspiring writers hoping to publish their work but are struggling to find themselves creatively?

Oh, what a lovely question, trying to find themselves creatively. I think the biggest thing I really believe is to write the work you want to write. Don’t think you have to write for a particular audience. Don’t think you have to write a particular voice. I was told early on if you’re chasing the trend, you are too late, right? If you don’t have something for the trend when it’s trending, you can’t chase it. So don’t try to write for what you think writing looks like now. And don’t try to write for some imagined audience that is sort of unpleaseable. Just write what you want to write. Write the weirdest stuff you want to write for the weirdos you want to read it, and your audience will find you, particularly in poetry, which can be so siloed anyway. Just pursue your weirdness and don’t worry about the marketing aspect of it.

Is there any question I didn’t ask you that you feel like I should have asked, or anything you just want to add?

I think the thing that I’d want to really emphasize is that I do think the book’s hopeful. When I was drafting this, one of my mentors was like, maybe this is great, but it’s pretty heavy, it’s pretty dark. And I went back to look at it, and it can be read that way. But the thing I told them, and I started rearranging the book in ways that tried to bring this out, is that it’s not just despair. The thing about writing an apocalypse is that there’s something that comes after. We would not write about the apocalypse if we didn’t believe there was someone on the other side of it reading the work. And so to think about apocalypse is to think about what comes after, and that makes it hopeful. There is hope in the work, and there’s hope in pursuing pleasure and poetry during just devastating times.

–Interview with Kate d’Arcy, WWPH Fellow, 2025

WWPH INTERVIEWS: VARUN GAURI, FOR THE BLESSINGS OF JUPITER AND VENUS

Varun Gauri was born in India and raised in the American Midwest. After studying philosophy in college and public policy in graduate school, he worked for more than two decades on global poverty and human rights, publishing academic articles and books on development economics and behavioral economics. He now teaches at Princeton University and lives with his family in Bethesda, Maryland. His short fiction was nominated for a Pushcart Prize and recognized in Best American Nonrequired Reading. He was a Summer Writer-in-Residence at Washington, DC’s The Inner Loop. For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus is his first novel. More about Varun Gauri at his website here.

What inspired you to start writing creatively, and specifically, to write For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus?

My parents tried to sell me on a Hindu arranged marriage like their own. I resisted outwardly (my first wife was Jewish) but somehow relented in spirit, essentially sleepwalking, not really believing that marriage was mine to choose, shape, and make. So the seed of the book was an effort to understand what had compelled me about my parents’ arranged marriage, and how and why I fought it. Eventually, I grew fascinated by broader questions about the interplay of compatibility, passion, and acceptance in relationships.

What was the most surprising thing you learned about Avi and Meena, your main characters, as you were developing them?

Originally, I conceived Meena and Avi as opposites. Meena was supposed to be romantic, witty, worldly, and skeptical of arranged marriage while Avi was practical, simple-minded, provincial, and traditional. It took me a while to realize I was writing a novel, not a fable. What helped was recalling a commandment from Bret Anthony Johnston, one of my writing teachers: “You will not do black and white. You will not have one character who is greedy and another who is generous, one character who is strong and another who is weak. Each of your characters will be greedy and generous, strong and weak. Complexity makes them interesting.”

What surprised me was that Meena and Avi, despite their differences, share something important. Both struggle against the dead hand of the past. Meena chooses arranged marriage because her late father, whom she loved, counseled her to. Avi is traditional because his parents are in thrall to an ideologue. Identifying and living their authentic desires and values is a shared journey for Avi and Meena, and recognizing themselves in one another is what gives their relationship hope.

What is your writing process/daily writing practice?

I like to write fiction with my first cup of coffee. I leave my academic writing for the afternoons. I find that I’m more imaginative in the mornings, less burdened by to-do lists and the state of the world. Also, for me, writing novels and short stories is more cognitively taxing than writing journal articles, and I like being fresh from a night’s sleep when writing fiction. Exercise also helps. When I find myself stuck on a plot point or an issue with a character, going on a bike ride sometimes provides clarity. Physical movement seems good for the imagination.

If you could be a character in one of your favorite books, who would you be and why?

Cosimo, in Italo Calvino’s The Baron in the Trees, is angry at his parents, so he climbs a tree and stays up there his entire life. I love trees and would love to live in one. I’m also envious of Cosimo’s determination to behave as stubbornly as he feels.

If you could be mentored by a famous author of the past, who would it be/what would you ask them?

Dear George Eliot — I love this line of yours: “But something she yearned for by which her life might be filled with action at once rational and ardent; and since the time was gone by for guiding visions and spiritual directors, since prayer heightened yearning but not instruction, what lamp was there but knowledge?” Your writing sparkles with your passionate desire for knowledge, for truth, and passionate inquiry gives your writing tremendous authority. How would you write with authority today, when we are often skeptical of knowledge, cripplingly aware of our own partiality, and unsure to which community our readers belong?

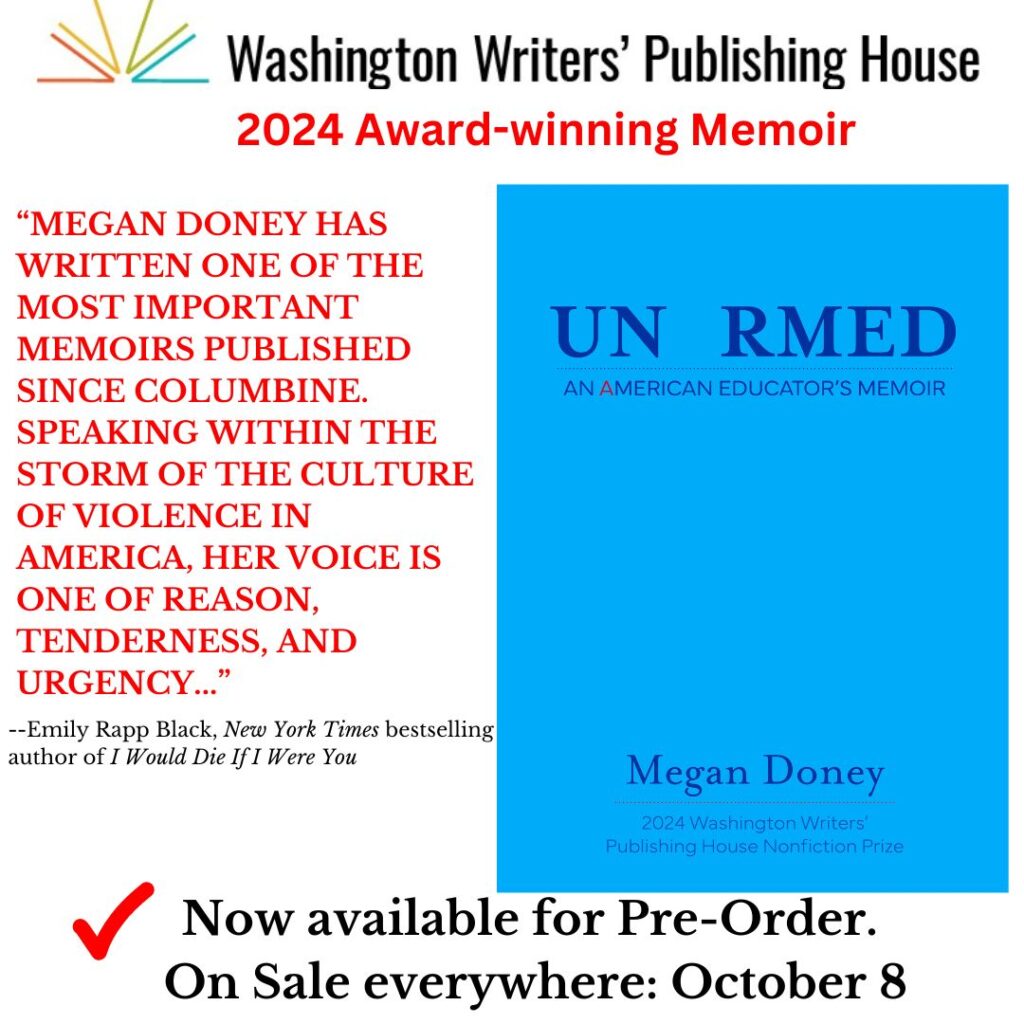

WWPH INTERVIEWS: MEGAN DONEY, author of UNARMED: AN AMERICAN EDUCATOR’S MEMOIR

Megan Doney teaches composition, literature, and creative writing at New River Community College in Virginia. Her work has appeared in Ilanot Review, Rappahannock Review, Creative Nonfiction, and other literary journals, as well as the anthologies Allegheny and If I Don’t Make It, I Love You: Survivors in the Aftermath of School Shootings. Doney was a Fulbright fellow in South Africa in 2007, and returned there in 2015 to study reconciliation and public narrative in the aftermath of violence. She earned an MFA from Lesley University. Unarmed: An American Educator’s Memoir is her first book.

What was the most challenging moment in your process of writing this memoir?

I can’t pinpoint a specific moment in the writing process itself; all of the writing was intellectually and emotionally challenging. However, I was very low after two failed connections with agents, being out on submission for more than a year, and multiple editors who basically said they thought the book was beautiful and important, but unsellable. In October 2023, I started sending the manuscript to small presses and contests and set December 31 as my final deadline; I would not submit it any further after that and I was prepared to junk it. Then, Caroline Bock from WWPH called me in January with the incredible news.

What do you hope educators like yourself will take away from this work?

I would like them to remember what brings them joy and meaning in their vocation. I believe teaching is sacred work and that learning alongside our students is a tremendous privilege. That said, I also hope that they will honor their boundaries and the limits of what they can and will do within that vocation. So much is asked of educators. It is too much to ask that they also assume mortal danger in their work.

What is your writing process/daily writing practice?

It depends on where I am in a text. I tend to think very metaphorically and associatively, and it takes me a long time to read, journal, annotate, and assemble my thoughts into something that (I think) might make sense. When actively drafting, I often use the Pomodoro method to stay focused. I’ve kept a journal my entire life, so I rely on that to work out my thoughts and have a tangible record of what I was thinking and doing at a particular moment.

What book/s are on your nightstand?

Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda; The Children’s Book by A.S. Byatt; Yellowface by R.F. Kuang; Once In The West by Christian Wiman; The Cross and the Lynching Tree by James Cone.

What advice would you give to anyone writing a memoir on a difficult subject?

Do not mistake writing for therapy. See T. Kira Madden’s article on this subject. The process of creation, and turning your experience into a narrative for an audience, demands that you, the writer, become your audience and balance distance with intimacy. Madden describes it as a kind of translation. The situation, as Vivian Gornick put it, is not the story.

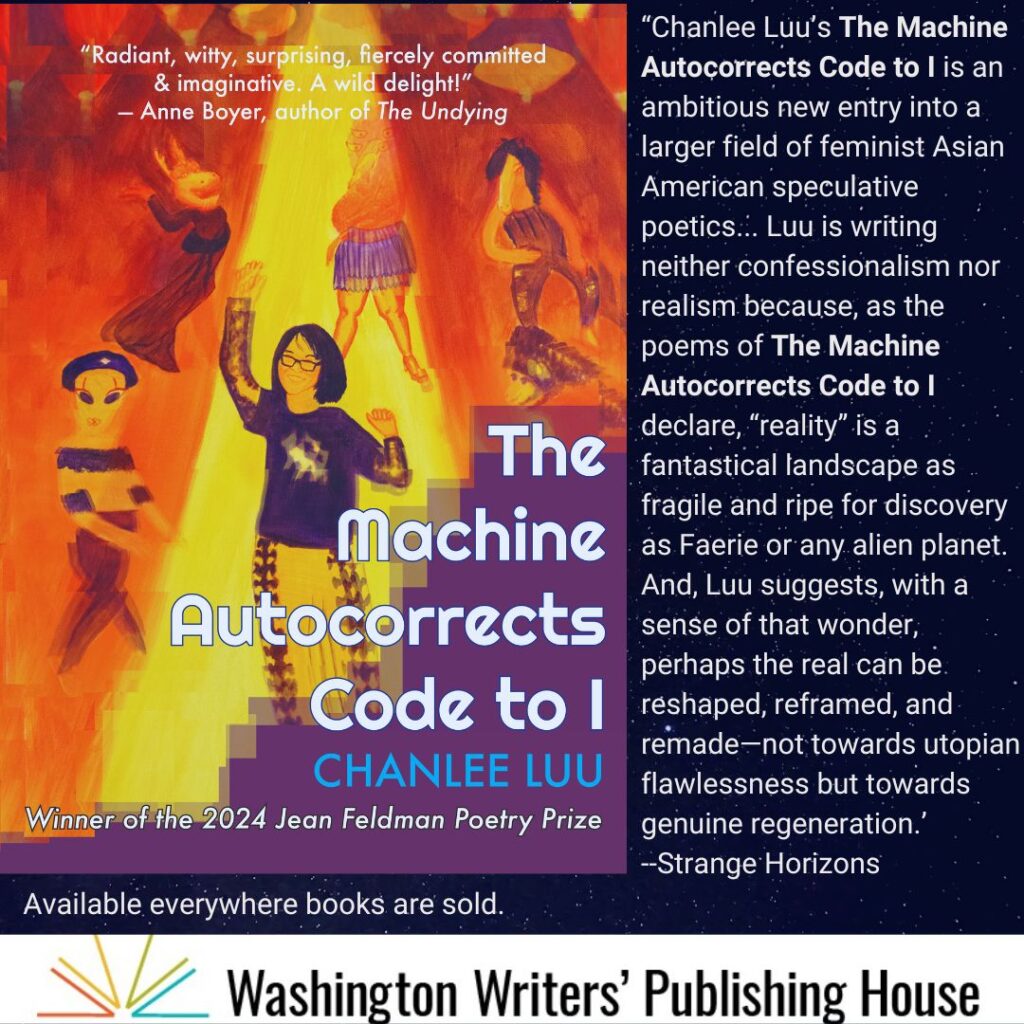

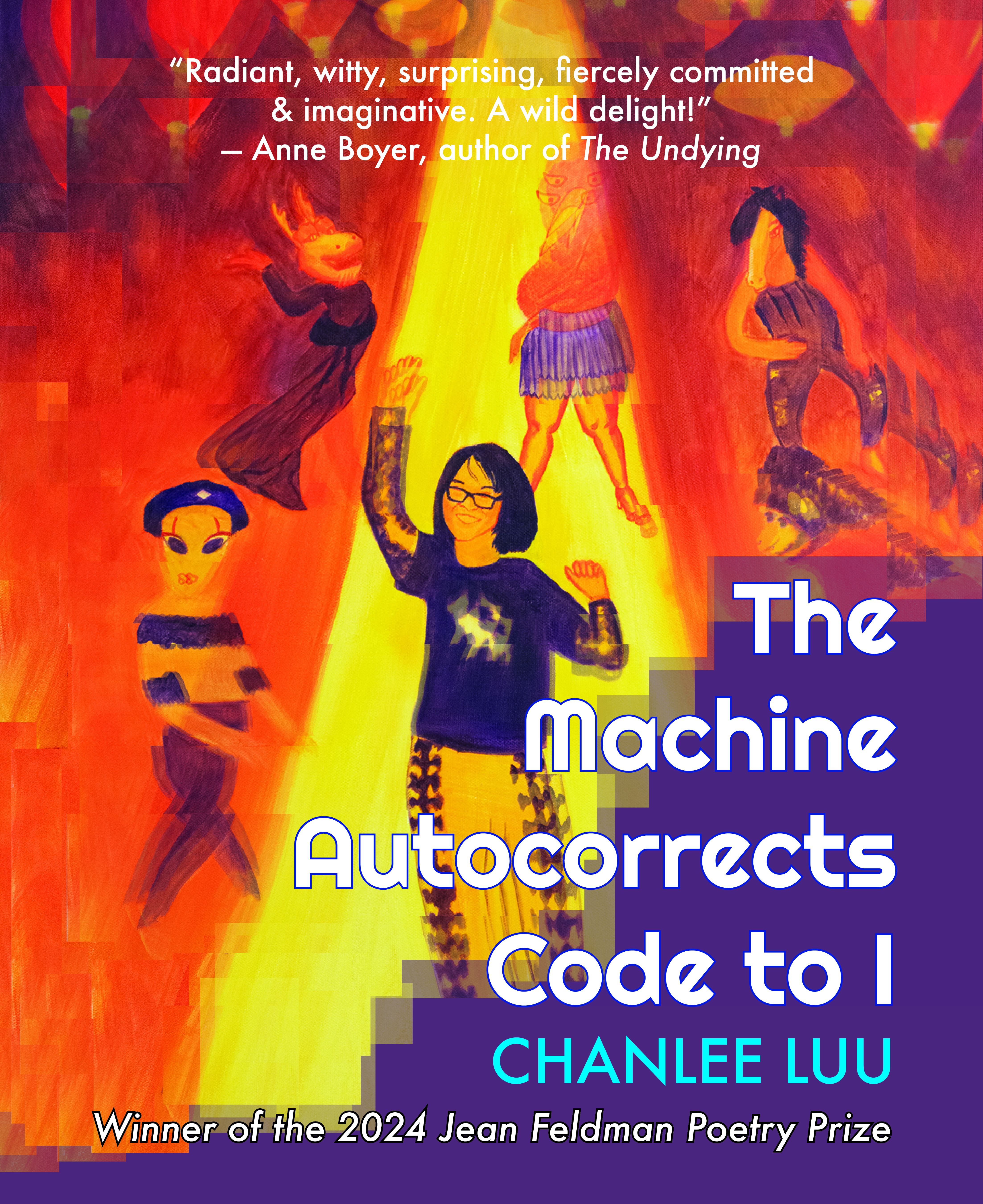

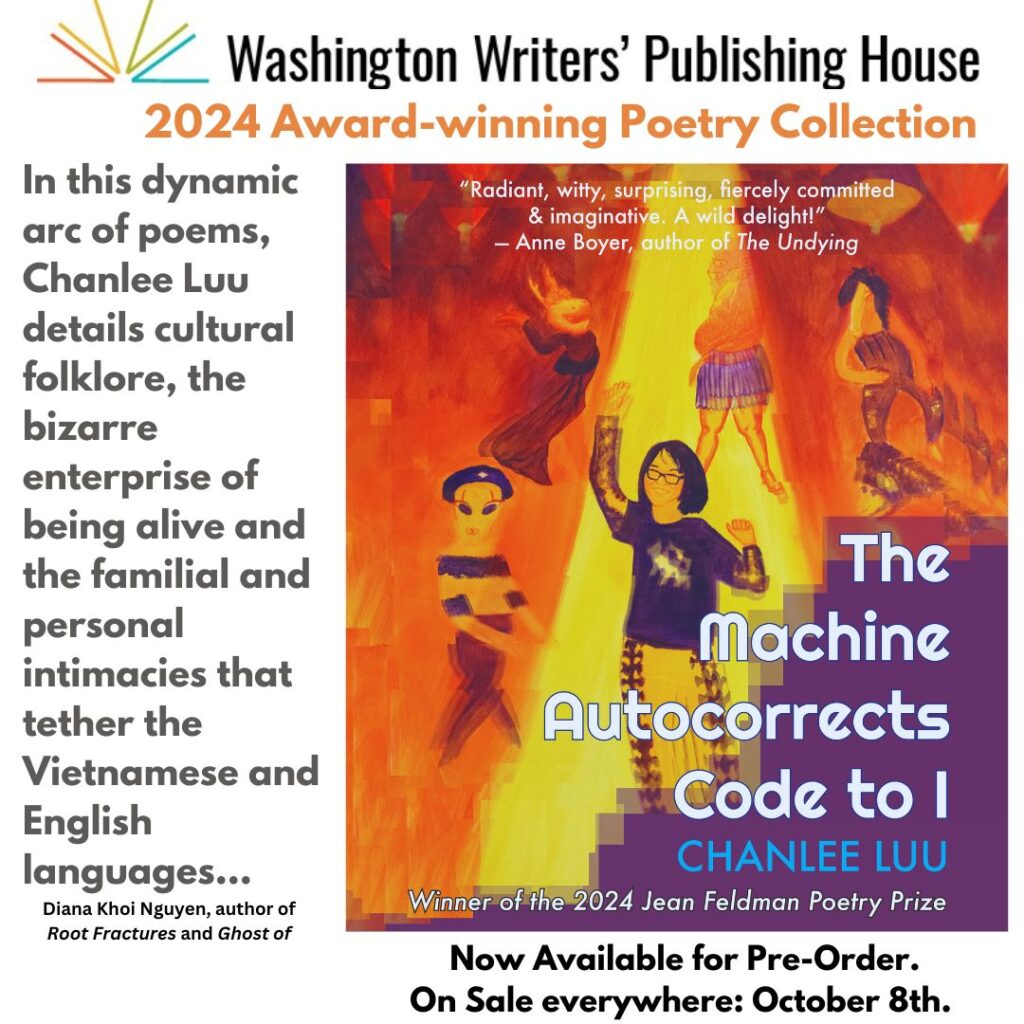

WWPH INTERVIEWS: CHANLEE LUU, author of THE MACHINE AUTOCORRECTS CODE TO I

CHANLEE LUU, winner of the 2024 Jean Feldman Poetry Award for THE MACHINE AUTOCORRECTS CODE TO I .

Chanlee Luu is a Vietnamese-Chinese American writer from Virginia. She received her MFA in creative writing from Hollins University, and BS in chemical engineering from UVA, where she competed in poetry slams. She writes about identity, pop culture, science, politics, and everything in between. She can be found on Twitter @ChanleeLuu, and her work in Snowflake Magazine, the gamut mag, Cutbow Quarterly, Tint Journal, Honey Lit, The Offing, and diaCRITICS, among others, all at chanleeluu.weebly.com. The Machine Autocorrects Code to I is her debut collection.

“RADIANT, WITTY, SURPRISING, FIERCELY COMMITTED & IMAGINATIVE…” –Anne Boyer, author of The Undying

From where did you draw inspiration for the title of your collection, The Machine Autocorrects Code to I?

The title comes from my Taylor Swift Golden Shovel about the process of healing, which we tend to think of as an individual process, but is actually communal. The title is open to multiple interpretations, but for me, the breakdown is: “The Machine” is late-stage American capitalism or any institution that oppresses its people; “Autocorrects” means we’re forced to go against our human nature; “I” refers to individualism. A colleague read the “I” as “one” and that works too! Overall, the book is about fighting these forces.

What was the challenge in marrying your STEM background and passion for writing and music in the pursuit of this poetry collection?

I think it was a very natural process, incorporating my multiple interests and backgrounds, which is the great thing about poetry— you’re able to seamlessly create connections between seemingly unrelated things. I think the biggest challenge was the murky area between scientific accuracy and creative liberties. For example, is coffee in our veins? No, but it is a common exaggeration for a person who drinks a lot of coffee.

What is your writing process/daily writing practice?

I don’t really have a daily writing practice right now with a full-time job and going to school, but when inspiration hits, I’ll write! I’ll usually use the structure of a form (or Excel!) to help me. I think rhyme gets a bad rap in contemporary poetry, but as Ange Mlinko says, “I let the rhyme have its way with me, because a more interesting stanza will come about that way, one I could never have planned with my rational brain. I believe in pattern, if nothing else, as an antidote to garrulousness.” I don’t write in rhyme as much as I used to, but I still think the constraints of a form force me to be more creative.

What was your favorite book as a child?

I loved Nate the Great books; I wanted to be a detective and solve mysteries and eat potato pancakes. My mom tried her best to find me a long coat that looked like his so I could dress up as him for school, and I did eventually use my detective skills to solve the case of “The Missing Homework.” No, a dog did not eat it; a classmate had erased my name and put his over it!

What literary figure, dead or alive, would you want to share a meal with?

How are we defining literary figures? There are 2 obvious answers. One is Taylor Swift, who I have been a huge fan of since 2006, and I would ask her how she Masterminds all the Easter Eggs. The other would be Ocean Vuong, who inspired me to pursue poetry further than just as a hobby. If we expand it to anyone who has ever written, I would pick my paternal grandparents, my Ông Bà Nội. I met my Bà Nội once when I went to Vietnam in the 2nd grade, and she was so full of humor and joy; I never got to meet my Ông Nội. When people tell me fond stories of their grandparents, I think “that must be nice.” So yeah, I’d like to cook with them, learn their recipes, and eat/laugh with them.