WWPH Writes: Issue # 39

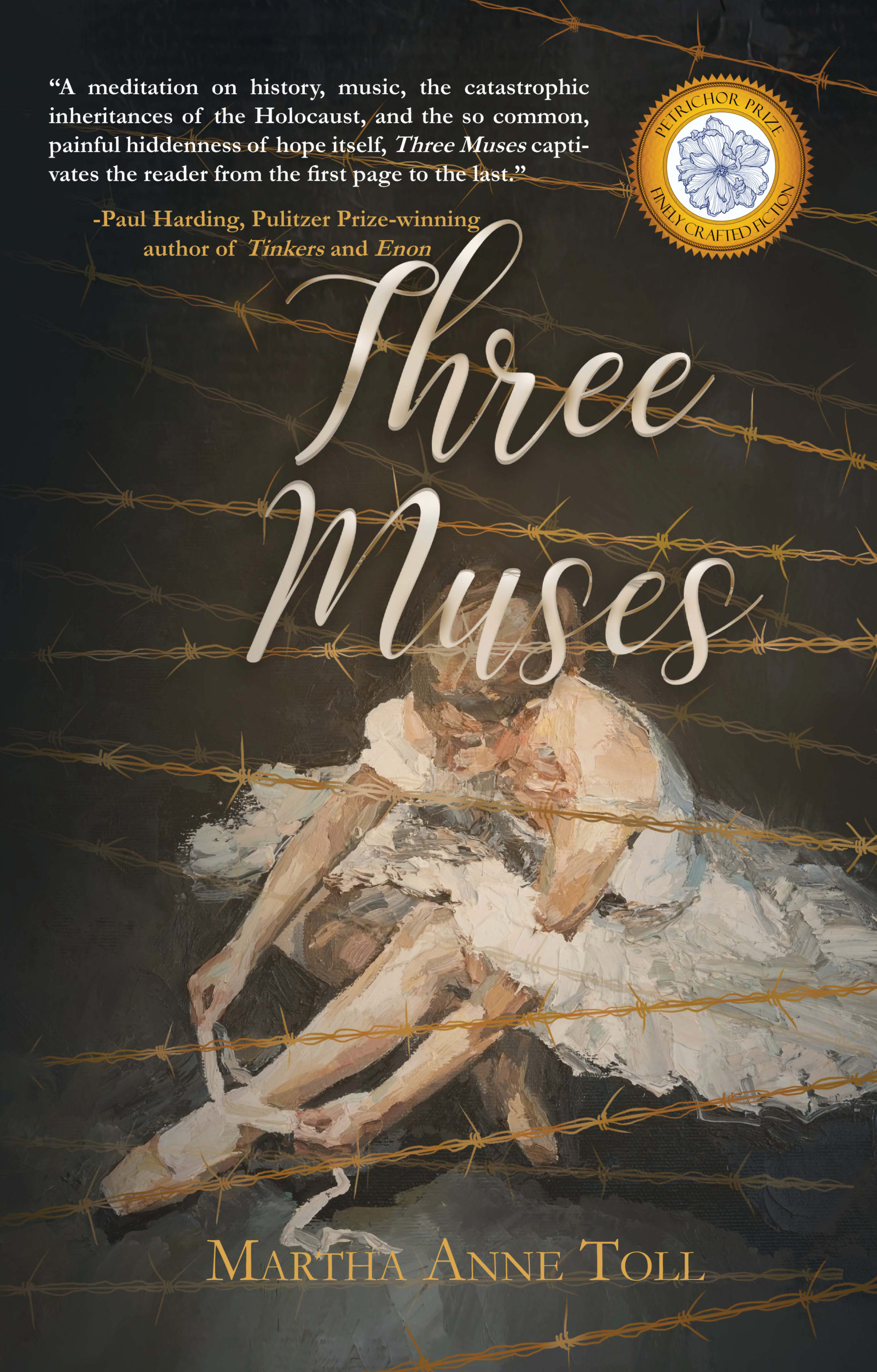

Welcome to Issue 39! In Nigel Assam’s “Halcyon Court (Backyard Trees),” the narrator describes the magic of a summer yard—speculating on the types of trees as the cicadas sing (something we may all long for now in the dark of December). In the excerpt from Martha Ann Toll’s acclaimed debut, Three Muses, we are also transported. This exquisite novel traces a love story out of World War II and the Holocaust to the unforgiving world of ballet, and we hope that these two short scenes entice you to read the entire novel from this Maryland-based novelist, book reviewer, and social activist.

We are also reading for our February issues. Surprise us with poetry and stories infused with love or winter, or both. And thank you to all who submitted to our second annual WWPH WRITES THE HOLIDAYS–we are overwhelmed by the creativity and productivity of our readers! Winners will be published in our next issue on Friday, December 23rd.

Jona Colson

co-president/poetry editor

WWPH Writes: Poetry

Nigel Assam is a Boston University Creative Writing graduate. Assam was born and raised in Trinidad until the age of fourteen when he emigrated with his parents and sisters to the United States, settling first in North Miami, Florida, then Yonkers, New York. Assam has lived in the U.S. for 30 years and currently resides in Baltimore where he works as a realtor.

Halcyon Court

- Backyard Trees

Midsummer sun attaches to the bark

and branches of tall, old trees whose names I

can’t utter since I don’t know what they’re called.

Is that a maple? Its leaves look Canadian.

That other one’s hanging like a willow,

but a willow it isn’t. That’s some kind

of evergreen. What’s an alder look like?

Is that an ash? There are no oaks, neither

is there a Bradford pear, nor a magnolia

whose petals, after just two weeks, litter

the grass-like paper. These trees were buzzing,

up until recently, with the cicadas’

otherworldly, high-pitched sound veiling

every day, that would be similar to—

if they exist—an alien spacecraft’s,

its spectrum of dazzling lights flickering

in colorful patterns, flashing for weeks,

to finish a vision that now we’ll have

to wait another seventeen years for.

Author’s note: only the first section of the poem is published here.

© Nigel Assam 2022

WWPH Writes: Fiction

Martha Anne Toll writes fiction, essays, and book reviews, and reads anything that’s not nailed down. Her debut novel, Three Muses, won the Petrichor Prize for Finely Crafted Fiction. Toll brings a long career in social justice to her work covering writers of color and women writers. She is a book reviewer and author interviewer at NPR Books, the Washington Post, Pointe Magazine, The Millions, and elsewhere. She also publishes short fiction and essays in a wide variety of outlets. Toll has recently joined the Board of Directors of the PEN/Faulkner Foundation. More at her website here.

Context from the novelist: This excerpt comes from the beginning of Three Muses. The novel opens in 1963 Paris. Dr. John Curtin is attending the World Congress on Psychiatry and Mental Health. The wife of his boss, Dr. Leventhal, hands John a ticket to see the New York State Ballet. For reasons readers will discover, music is deeply traumatizing to John, but he cannot refuse the ticket. When the curtain lifts, he becomes smitten with ballerina Katya Symanova, dancing the Muse of Discipline in the ballet Three Muses. The second part of the excerpt shows Katya’s experience of debuting Three Muses in Paris. Thank you for reading!

THREE MUSES

Paris 1963

John settled into a bench at the edge of the plaza. Dusk was gray-pink, backlighting the Opéra. Balletomanes were arriving—tuxedoed men with stylish women on their arms. It wasn’t just the evening gowns, or the way women draped their shawls. Their pacing and carriage were glamorous too. Each with a distinctive walk; together, a pageant. If he weren’t answerable to Dr. Leventhal, John would have disposed of Mrs. Leventhal’s ticket. He’d much rather spend the evening out here.

Inevitably, he went inside. He picked up a program and made his way to the first balcony. The orchestra warmed up as a chorus took their places in the side boxes.

The music began: slow, plangent tones paced to the speed of a man’s forward tread. The chorus entered—deep and serious and sad—as if their voices had taken the measure of John’s memory. The curtain lifted on a snow-covered mountain against an aqua sea, a scene to conjure myth. Dancers in blue and green leapt in unison, legs like arrows, arms overhead. They fell into lines fracturing like kaleidoscope patterns, or forms in opposing mirrors.

Overcome by jet lag, John dozed off. He was in his family’s Mainz living room: Mutti darning socks, Papa with his pipe— left thumb over the bowl, right poised to cock his silver lighter. Lopsided smoke rings meandered toward the ceiling. A few more puffs before the pipe hung limply from Papa’s mouth as he grew increasingly absorbed in the evening paper.

Rubbing his eyes, John slowly woke up. He knew the music. After dinner, when Janko’s schoolwork was finished and he was getting drowsy, Papa had played it on the gramophone. If Janko was lucky, he’d be permitted a few minutes to sit with the grown-ups before Mutti declared bedtime.

The chorus sang with veneration, permeating the hall the way the smell of Mutti’s bubbling apple strudel filled her kitchen, or the first peaty drafts of Papa’s pipe suffused the living room. John was flooded with grief, the music a piercing shorthand for what was gone: all of them. Mutti, Papa, even little Max, who hadn’t been born until later. John had not thought about this music in decades, if ever. He recalled Papa starting the gramophone as Mutti settled into the horsehair sofa with her sewing kit. Janko was growing so fast, Mutti had to let out the hems of his trousers. The sewing kit was black walnut, the varnish on the edges smoothed from use. (It was from Janko’s grandmother.)

The orchestra moved with gravity and purpose, music as familiar as childhood. Now it was named. Mozart’s Requiem. Not only the people and the place, but this, too, had been stolen. John didn’t need to stay. Dr. and Mrs. Leventhal would understand. Searching for the quickest exit, John struggled to call up something—anything—to stanch his anguish. What value were his sessions with his training psychiatrist? Dr. Roth was useless.

None of the patrons around John budged; he would be imprisoned here until the end of the act. Making another effort, he took a deep breath to marshal his defenses.

And then.

A lone ballerina sheathed in white floated toward center stage. The audience greeted her with shouts of “Brava!” She was the Muse of Discipline. She cut through the whirling dancers with precision and exactitude. John had never seen anyone so exquisite. She was a reverie, an evocation of grace. Each fluttering arm motion dissipated his pain. Her dancing ordered the music, rendered it alluring. He strained left as she exited, as if by craning his neck he could follow her.

She spun in duo with the Muse of Song, summoning peace and beauty. Together, the two made harmony. Their playfulness lightened John’s mood. He glowed like a man feeling desire for the first time.

+

Lars, playing the Old Faun, stood with Katya, readying their entrance. Adjusting his horns, he whispered ballet’s favorite good luck term: “Merde, Muse of Discipline.”

“Thanks, Lars. You too.”

Mr. Yanakov paced the opposite wing, scowling. Head down, he gave the impression that his company had just suffered appalling notices, and not that they were, instead, poised for opening night before the cream of Paris. Katya felt it imperative to gather her forces and ignore him. She fingered her tutu netting and shook out first her right leg, then her left. Three Muses in Paris. Katya was relieved for the vast physical expanse separating her from her choreographer.

And the expanse between her and Mama? Mama had never even seen Katya dance. Her absence was enveloping, a reminder that despite being embedded in the company and despite Mr. Yanakov—who had willed Katya the stage, conferred on her this feast—Katya danced through life alone. Her memories had grown hazy with time; a few: Mama’s toothy grin when she handed her daughter her school lunchbox; Mama’s throaty laugh, her butterscotch housedress with the white rickrack. For years, Katya kept up an ongoing monologue addressed heavenward, as if her soliloquies could coat the void that was Mama.

“Places!” the stage manager called.

Katya made a last adjustment to the ribbon on her right pointe shoe and felt the house, feverish with anticipation.

Act One began.

Katya leapt onstage, parting the dancers as if her luminous heat would grill them alive. To dance was to live. To till motion; to impart the joy that welled up every time she took to the stage, her body the vehicle for her art. The lights were blinding. As the music intensified, she skimmed the energy from the audience to breach another dimension. Transcending reason, she danced through raw emotion and spun toward a new center.

Reprinted with permission of Regal House Publishing © 2022.

Purchase Three Muses everywhere books are sold including at Politics & Prose in Washington D.C.

WWPH Community News

*SUBMIT TO WWPH WRITES…We are seeking poetry and prose that celebrate, unsettle, and question our lives in the DC, Maryland, and Virginia areas (DMV) and our nation. We seek lyrical and dynamic work and believe in cultivating a diverse and inclusive environment of content, form, risk, and experimentation. New perspectives and voices with craft and fierceness are strongly encouraged to submit. It’s FREE to submit, but you must live in the DMV. We are reading right now for February 2023 — if you have something that will surprise us about love or winter– Submit here.

*DONATE TO WWPH...In this season of giving, please consider donating to the Washington Writers’ Publishing House. We are a cooperative, all-volunteer press and a 501c3 charity. All donations are tax-deductible. Even more, all donations go directly to programs that support publishing writers from Washington DC, Maryland, and Virginia. If you are thinking of a special donation to WWPH, consider sponsorship/naming rights to our annual fiction and creative nonfiction prizes. Donate here. More questions? Contact Caroline Bock and Jona Colson at wwphpress@gmail.com.

GIVE A BOOK BY A LOCAL AUTHOR THIS HOLIDAY...especially our 2022 award-winners: THE WITCH BOTTLE & OTHER STORIES by SUZANNE FELDMAN and YOU CANNOT SAVE HERE, winner of the 2022 Jean Feldman Poetry Award, by Anthony Moll. The WASHINGTON WRITERS’ PUBLISHING HOUSE has a Bookshop! BUY OUR AWARD-WINNING BOOKS and help us keep this nonprofit, cooperative, literary press strong for writers and readers like you. Click here and browse all our titles at our bookshop.

Thank you for being part of the WWPH Community! Look for the winners of our

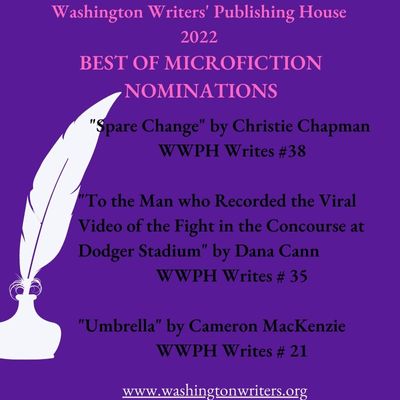

WWPH WRITES THE HOLIDAYS next issue on December 23rd!

Caroline Bock

Fiction Editor, WWPH Writes

President, WWPH

Jona Colson

Poetry Editor, WWPH Writes

President, WWPH