WWPH WRITES ISSUE 68

Welcome to issue 68... we are amplifying the works of two writers with celebrated new books, poet Simon Shieh and fiction writer Elizabeth Bruce, and announcing the winners of our 2024 manuscript contests. We are grateful to all who shared their fiction, nonfiction, and poetry manuscripts with us. There is so much literary talent in the DMV! This year, like last, all in our 2024 press slate will be debut works. Look for them to be published in October 2024. More details below.

Our judges, past winners of the manuscript contest, read for weeks, and we greatly appreciate their effort as well. As you know, WWPH is uniquely a cooperative (all-volunteer) small literary press. It is the continued interest that our press-mates–and that you, our readers, have to engage with a wide range of diverse DMV voices, that excite us, and keep us wanting to pay it forward.

Read on!

Caroline Bock & Jona Colson

co-presidents, WWPH

WWPH WRITES POETRY

Simon Shieh is the author of Master (Sarabande Books, 2023), chosen by Terrance Hayes for the Kathryn A. Morton Prize. His poems and essays are published in Poetry, American Poetry Review, Best New Poets, Guernica, and The Yale Review, among others, and have been recognized with a National Endowment for the Arts Literature fellowship and a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation. He lives in Washington, DC.

ABSOLUTION I walk to the river empty- handed except for a cup of coffee, whisper into the dark, forgive me my manhood. I pour the coffee into the river but only the milk spills out splashes into the water like a bolt of lightning. No matter how hard I try I cannot see all of the dark at once. And I know how the sky lies to us in the rain. But the snow, the snow must be a confession.

Available everywhere books are sold. More details at Sarabande Books here. Reprinted with permission of the author. ©Simon Shieh 2024

WWPH WRITES FICTION

Washington-DC-based Texas author Elizabeth Bruce’s new short story collected, Universally Adored and Other One Dollar Stories, (Vine Leaves Press, 2024) gives readers 33 ways of looking at a dollar.

Her debut novel And Silent Left the Place, won Washington Writers’ Publishing

House’s Fiction Award and distinctions from ForeWord Magazine

and Texas Institute of Letters. She’s published in the USA, UK,

Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Malawi, India, Yemen, and The

Philippines, A co-founder of Sanctuary Theatre, her bilingual book,

CentroNia’s Theatrical Journey Playbook: Introducing Science to

Early Learners through Guided Pretend Play, garnered four indie

awards. She’s received the DC Commission on the Arts & Humanities

and McCarthey Dressman Education Foundation Fellowships

and studied with Richard Bausch, Lee K. Abbott, Janet Peery,

John McNally, and Liam Callanan. Photo credit: Nicolas Ortega.

From the author on this excerpt:

“Baltimore’s Visionary Art Museum expands “the definition of a worthwhile life.” So too does ‘All Knowledge.’ It honors the resonance of the reader’s response: “The world of reality has its limits,” Rousseau states, but ‘the world of imagination is boundless.’ ‘We do not enter the book so much as the book enters us,’ says scholar Theodore L. Steinberg, so, here’s to reading as a transformational act.”

ALL KNOWLEDGE

One dollar.

Theo had tried to think about moving, about rejoining his brothers in the city or his sisters in the suburbs like they swore he must, but each time he’d tried, each time he’d laid his book down and walked to the dresser by the window to pack, he’d seen it.

The sign: All the Great Books You Can Carry–$1.00

Two years into his grand adventure, his great escape from the hustle, the relentless roar of ambition that ricocheted around him, that menacing world his parents and teachers and siblings insisted was the best and only path in life, that sign still made him swoon.

All the Great Books You Can Carry–$1.00

Oh, what a feast it had been, a banquet, a fete. And wasn’t it still? Nevermind what they said, what his sisters and brothers proclaimed as the truth, about money and meaning and the real world and all. Why can’t it go on, he thought and rethought, this banquet of stories, for the rest of my life?

Theo looked again at the certified letter that had arrived that morning from his sister’s lawyer. “You are hereby mandated to appear…,” it said and summoned him for a “Compulsory Psychological Evaluation” at such and such a date and time and place.

And there, taped to the envelope was a note from his landlady: What does this mean, Theo? she’d written in her wobbly hand. Are you in some kind of trouble?

He felt faint and slumped down in front of the sagging mahogany drawers, filled with the corduroy pants and t-shirts and sweaters he’d worn all these years. He closed his eyes and lay flat on the floor the way he had as a boy when the world was too much with him then as it was now. He ran his long fingers over the ribs of the braided rug that stretched from the bed to the dresser. His stomach churned as it used to do in the libraries of his childhood, and he curled his bony knees up under his chin.

He’d done it again, he realized, forgotten to eat. “Now Theo,” his mother used to scold him. “Put that book down, child, and eat. A growing boy needs real food, not just food for thought.”

“Not now, Mom,’ he’d tell her, the high seas pounding his ears, Quequeq’s coffin bobbing before him. “I am Ishmael, just let me be!”

His stomach growled again, and Theo opened his eyes. In his sparsely furnished room, stacked all around the walls, jammed under the dresser, and behind the box of letters from his family were his treasures, his prizes, keepers of all knowledge, his true and only friends. Borges and Rumi, Pushkin, Camus, Dunbar and Orwell, Maugham, Angelou. Gently, he slid a stack out onto the expanse of the floor. Nestled behind them, in neat, perfect rows were their brethren–Goethe, Gibran, Baldwin and Bontemps, Bradbury, Hughes, Cervantes and Ellison, Achebe and Dante, Toomer and Homer and Woolf.

“I can’t do it,” he whispered, his heart again burdened. So much sorrow they’d been through, he and his heroes. So much strife and betrayal. War and rebellion. Redemption and love. “I can’t leave you,” he said, stroking their spines.

He sat and looked through the letters, pleading with him over the years to stop his bookish nonsense and come back into their world.

“Dear Theo,” the letters always began. “Enough is enough, bro,” his brother Andre had written.

“You’re squandering your college,” wrote his sister Renee.

“Think of your mother,” his father had begged him.

“Come home, my sweet Theo,” his mother had implored. “We’ll find you a righteous real job.”

“Don’t make us do it,” his sister Wanda had said, her bossy big-sister voice coming through in her words. “We will meet with that lawyer. We’ll do it. You have got to come home.”

Theo thought of Ivan Denisovich in his Siberian gulag, clutching his crust of bread, taking joy in the smallest of pleasures: the butt of a cigarette, a small bowl of kasha, a moment of sleep, and Theo knew his family was wrong. They were all wrong.

Here, Theo thought, in this room, it is warm, is it not, and he gave a sweet, silent thanks to the old man and old woman who swapped him this room and his meals for some labor, such as it was, mowing grass, chopping wood, hanging wash.

Simple work, simple life.

He thought of the diner where he swept up off and on, for a dollar or four or a hot cup of joe at the counter to crack open a new book.

What more do I need?

He breathed in and thought of the blind poet Borges and his labyrinths, and of Tillie Olsen standing there ironing. Of Toomer’s women living alone in the thin strip of land between the tracks where the pines sing to Jesus. Of the Invisible Man with his hundreds of light bulbs in his underground room, and his heart ached the ache of a thousand stories held close while the wind hurled itself against the night and the sparrows sought refuge in the splintered wood outside his window.

He closed his eyes and Whitman, leaning and loafing at his ease, summoned him to lie down among the blades of summer grass.

“The beautiful uncut hair of graves,” Theo muttered and kneeled on his knees. He slid the yellowing stacks of paperbacks back under the dresser, lining them up in quaint even rows like potted pansies. “Tenderly will I use you curling grass,” he whispered, and fumbled in his pocket.

There, crumpled between a book of spent matches and an Indian penny he’d found on the road, was an old dollar bill, change from the five-spot he’d made Monday sweeping the diner’s front porch.

“One dollar more.” He rose to his feet and checked the clock on the wall. One hour before the bookstore closed.

One hour. One dollar.

For all the knowledge in the world.

Theo ripped up the summons, put on his jacket and headed for the door.

Universally Adored and Other Dollar Stories by Elizabeth Bruce is now available everywhere books are sold. More details here Used with permission from the author © 2024

WWPH NewS

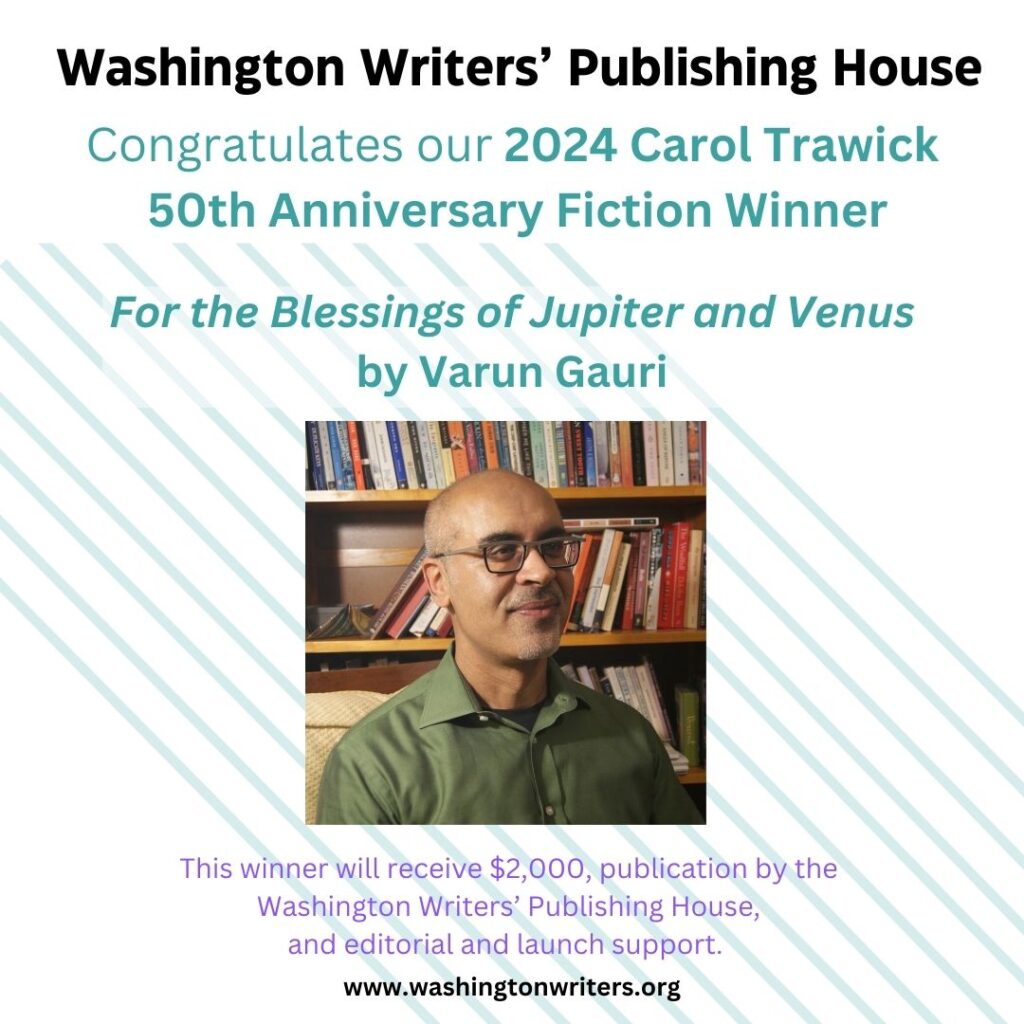

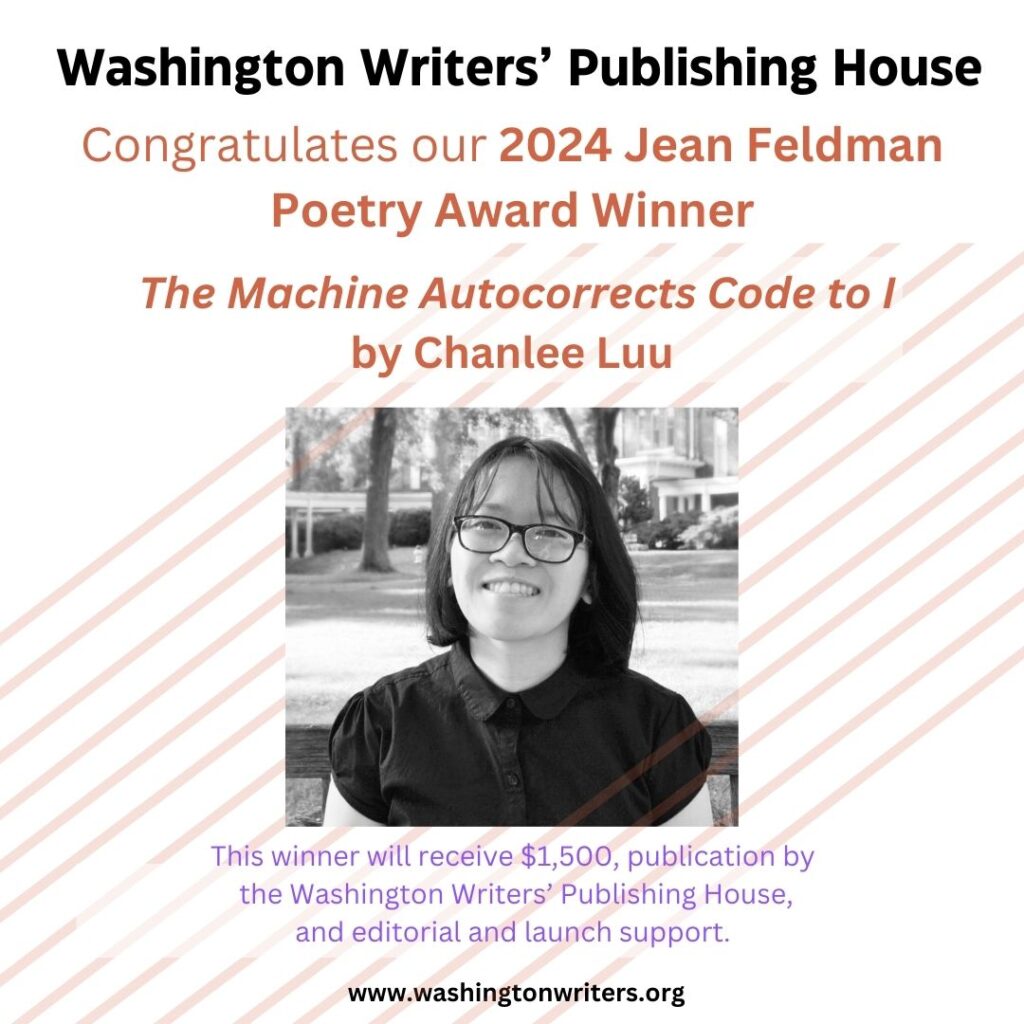

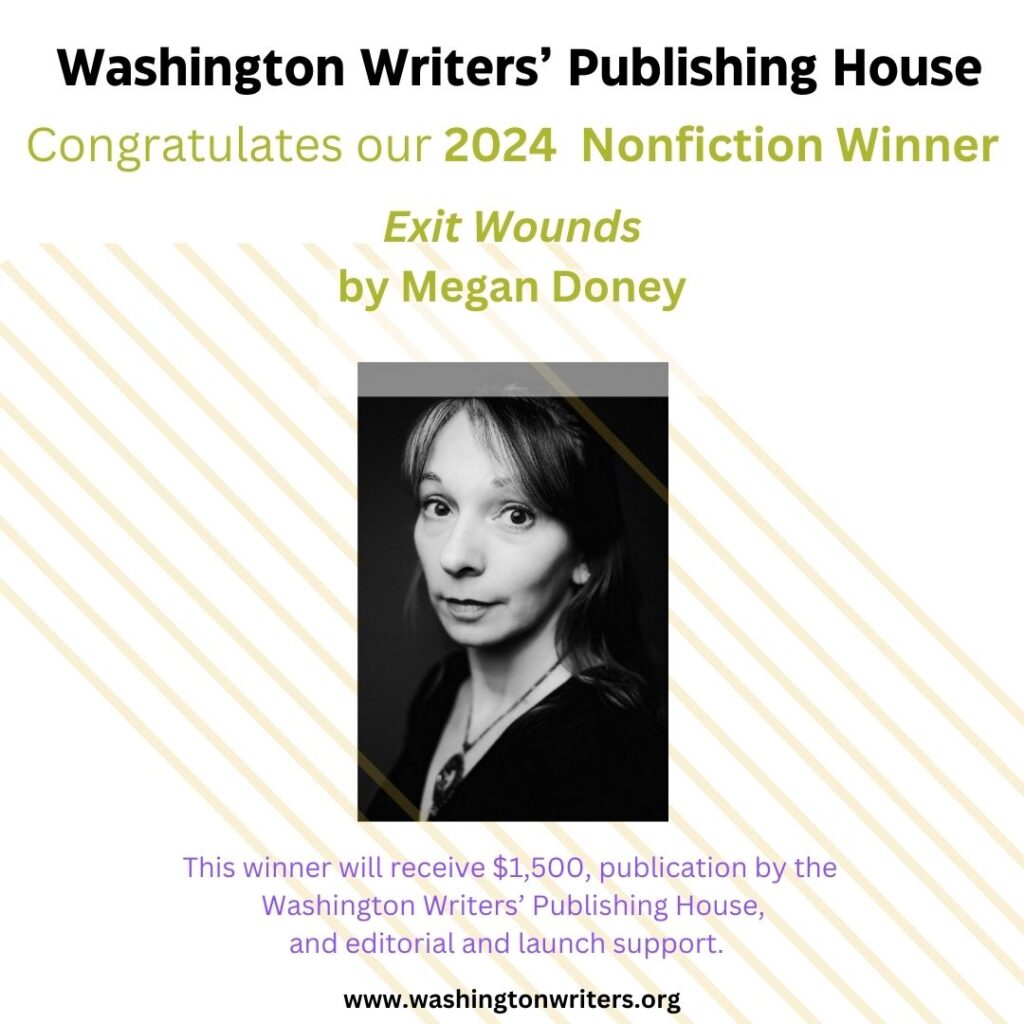

Announcing our 2024 manuscript winners…look for their books to be published in October 2024…

Our 2023 Award-Winning Books continue to garner attention and acclaim. They are available everywhere books are in trade paperback and for Transplant: A Memoir and Bad Questions in ebook as well! Support your local independent bookstore and your WWPH by ordering them from www.bookshop.org.

A Special Shout-out to DC Trending for their review of BAD QUESTIONS this month. They called this novel set in the early 1970s in Montgomery County, “immersive.” And here’s more, “While there are numerous touching and unexpectedly humorous moments in Bad Questions, what really stands out is the novel’s structure. Kruger writes an effective prologue and epilogue, introducing us to an older, wiser Billy, a Billy who has been molded by the profound questions he once posed and has evolved into a scientist who now makes a living by asking interesting questions. Outside of these introductory and concluding sections, Kruger steers clear of retrospective narration, effectively removing the influence of hindsight on the majority of Billy’s narrative, enabling Bad Questions to be a truly immersive journey.” Read the entire review here (and buy a copy today!).

A Free PRIDE Poetry Workshop is offered with the National Arts Club in D.C. on Thursday, March 21st at 6:30 pm with poet Ishanee Chandee. RSVP here. And a heads up: WWPH Writes will hold our third annual PRIDE Poetry and Prose Contest again this year. Submissions will open in May and publication in June. Cash prizes! This year we are encouraging LGBTQ+ allies as well as writers to submit. Keep reading WWPH Writes for details.

SUBMIT to WWPH Writes. We are reading now for our summer issues. We are eager for new voices! We are an inclusive, writer-driven community and want to see your poetry and prose (1,000 words or less). Free to submit. Send us your work via our Submittable link here.

Big Thank You to Solid State Books for hosting our first-ever WWPH Literary Salon. In short, it was fabulous! Thank you to the DC Writers who participated, with a special thank you to workshop leaders and readers including Regie Cabico, Susan Scheid, Dine Watson, Len Kruger along with Jona Colson and Caroline Bock. We will have our second WWPH Literary Salon in July at the National Arts Club in DC. So, keep reading WWPH Writes for details! The WWPH Literary Salons are made possible with a grant from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities.