WWPH WRITES ISSUE 71

WWPH Writes 71…features two works with hints of wonder and bits of magic–Discarded Shards by Eva K. Sullivan and a novel excerpt from Bookstories by Sarah Tollok.

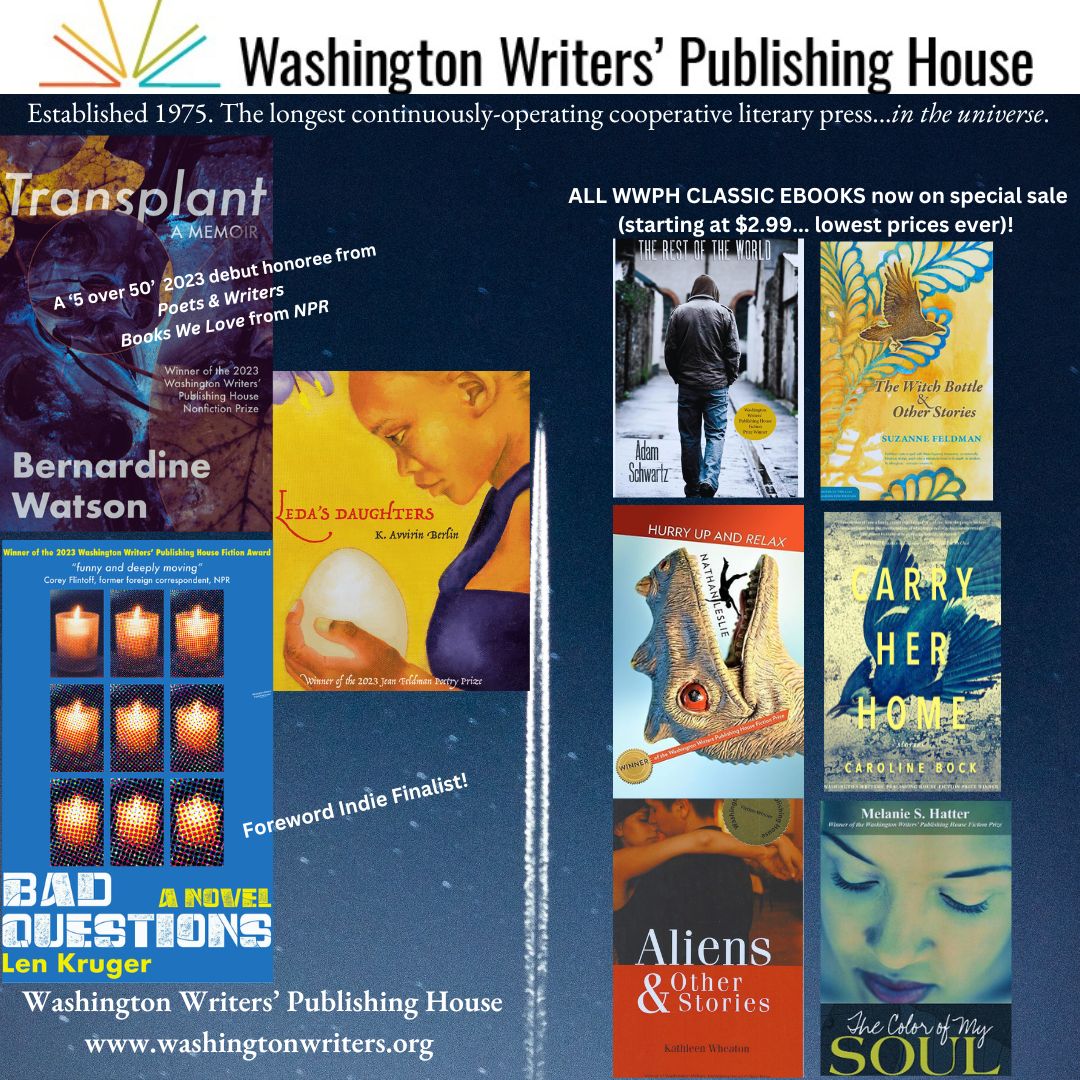

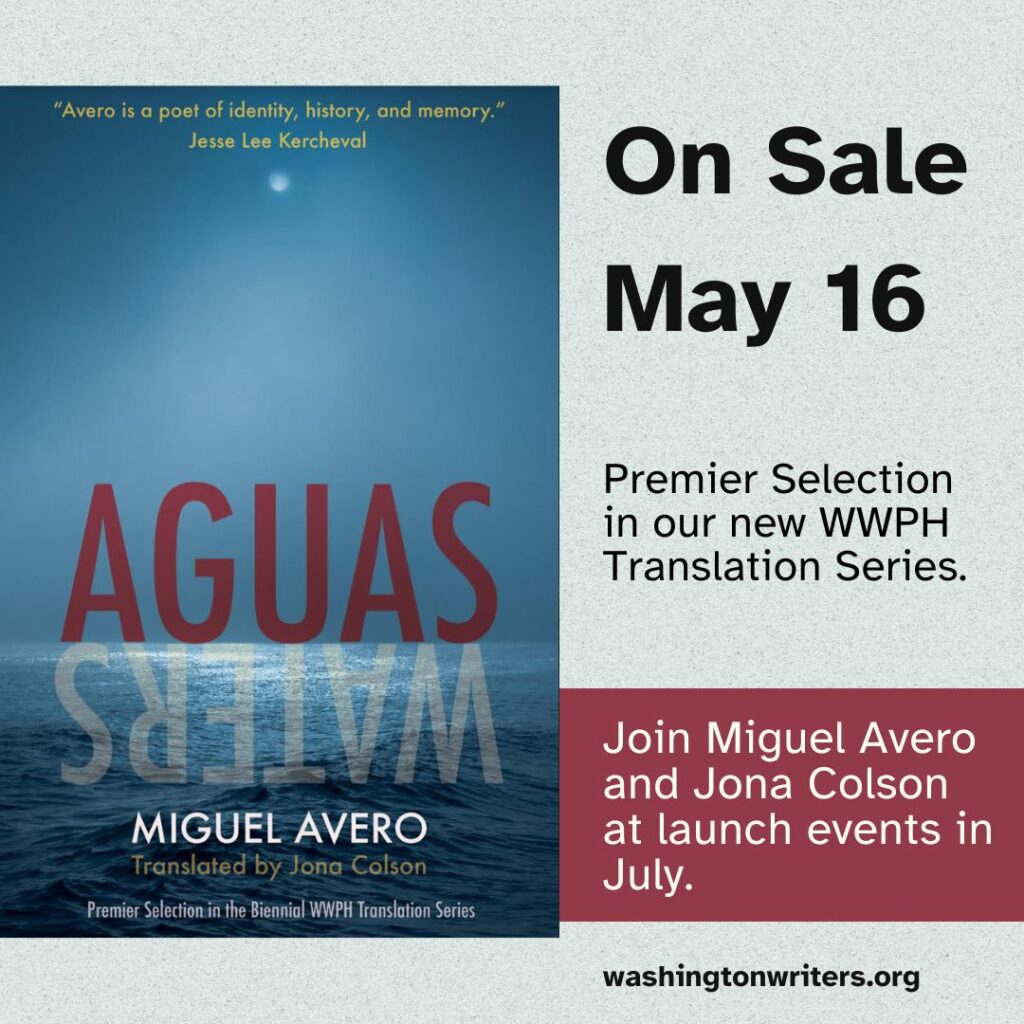

We have a busy spring ahead at WWPH! We are thrilled that our premier work in translation, AGUAS/Waters by Miguel Avero, is soon to be published (May 16th)–see below. Find us at our table at Kensington’s Day of the Book ( April 21) , Gaithersburg Book Festival (May 18), and at Capital Pride (June 9).

Happy National Poetry Month!

Caroline Bock & Jona Colson

co-presidents, WWPH

WWPH WRITES POETRY

Eva K. Sullivan teaches English at Richard Montgomery High School in Rockville, Maryland. She has written short stories, poetry, essays, and a memoir.

Discarded Shards

I pulled out pots of depleted soil

from years of primroses and pansies planted in the light of our dappled deck.

Every spring I was hopeful

that the leafy forest would let sunlight linger.

I potted, watered and plucked the droopy petals

as the days grew longer,

even though I knew that by August, shade would shroud the shoots.

The petunias palled and their rangy stems reached right off the edge.

Last year my friend’s gift of gardenia bloomed beautiful

then died for lack of light.

When the April sun came this spring

I was ready for flowers.

It had been the coldest winter in forty years.

But my husband said that our marriage had no future.

So… when the old oak fell across the picnic table

and totaled two cars, I knew that it was over.

I went into the shed and shook all the loose soil

from plastic pots stacked up on the shelf.

Into the dark woods, I flung the fragments of forgotten filler –

slivers of old ceramic saucers in parched potting soil.

At the bottom of each terra cotta pot, I picked out the shells

from our beach trip when the boys were little,

and tried to remember if they were from Maine or Delaware or

the time we had a family reunion in Florida.

Deep in the woods I discarded shards of broken Blue Danube dishes

from when my husband lived in Japan as a child.

I piled up the motley pots for a yard sale next month.

Let these empty vessels hold someone else’s hopeful blossoms.

Now one lonely fern flows from a pretty porch planter out back,

a reminder of the years before the woods grew dense

and leaves blocked out the light.

Out front, the neighbors’ flowers are the most beautiful I have ever seen.

I don’t know who will get the house.

©Eva K. Sullivan, 2024

WWPH WRITES: A NOVEL EXCERPT

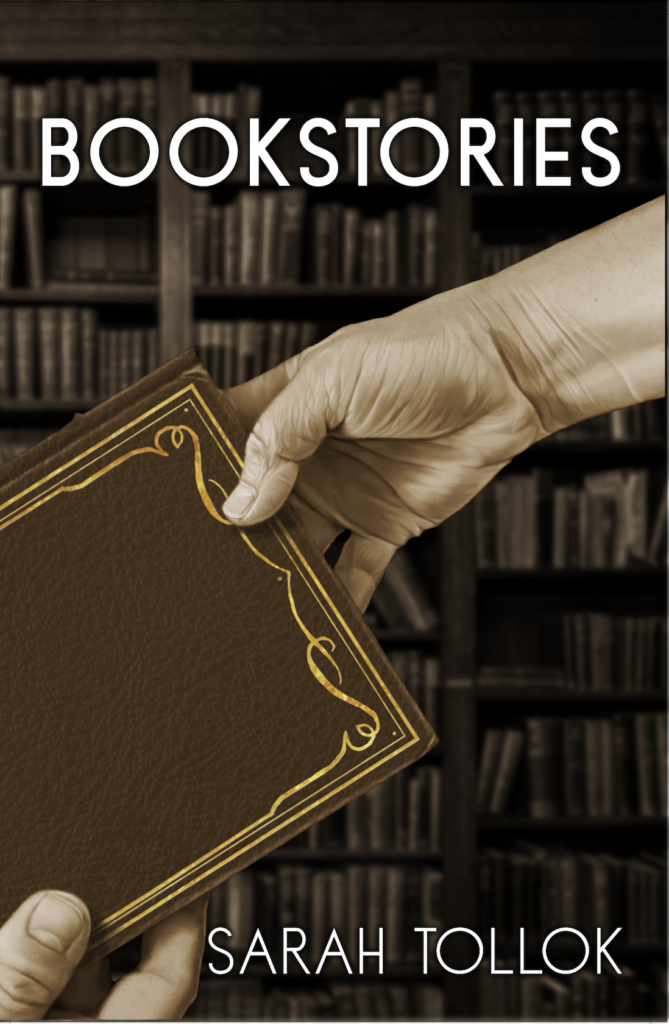

Sarah Tollok lives in the beautiful Shenandoah Valley of Virginia with her husband and two sons. She has work featured in anthologies with Improbable Press, Alan Squire Publishing, and Cal Destine Press. Her first novel, Boostories, debuted in March, 2024.

Author’s Note: The year is 1960. Junior editor Dottie Fletcher is elbows-deep in the slush pile at Tandem Bike Publishing. All of Dottie’s colleagues know her to be a book lover, but what they don’t know is that she has a special intuitive gift, one that gives her insights in a writer’s life just by reading their words. Every day, Dottie hopes to find an envelope from a brilliant writer who keeps sending in stories without endings. This mysterious author also never signs their work, and even with Dottie’s extrasensory ability, she can never get more than a whisper about them.

BOOKSTORIES

The writing was so brilliant that it required reverent silence. Reading this author’s work made Dottie feel like she was standing near the huge bank of votive candles at St. Pat’s Cathedral, surrounded by soft, warm illumination. Each flame an intention all its own, but together they created something beautiful: a whole bigger than the sum of its parts. Enough to warm someone looking for more than physical warmth on a cold, lonely day.

Dottie flipped through the pages faster and exponentially faster, like gravity pulling, tumbling young Alice down the rabbit hole. And then, like always, just when she was thoroughly lost in the story, she reached the end of a page, and there was no more.

Dottie’s descent into Wonderland abruptly jerked to a stop. She was left hanging there, suspended among the teacups and pocket watch gears, unable to set even one silk-slippered foot into the Mad Hatter’s party, or anywhere else.

The story didn’t have an ending.

None of them ever did.

Dottie handed off the manuscript to Gail and Ted then slumped onto the corner of Bobby’s desk. The story, like the author’s other submissions, was incredibly real and immersive. Dottie felt like she could hear the water of the Hudson lapping against the pilings below the dock, smell the oily smoke from the ship engines. But any sense of the author themselves? Nothing. It was maddening.

“Wow, right?” Bobby asked.

Dottie nodded, then walked back to her desk to get a new cigarette. Before she could dig one out of the pack, she glanced down at the submission she’d been reading before Bobby sounded the alarm.

The story was a romance set on some island in Alaska. The writer’s cover letter spoke of how everything Hawaiian had become a fad since the island’s recent ratification as a state. She felt that Alaska, also having just officially joined the US of A, was equally deserving of some love and attention.

Dottie thought the writer had a point. The Alaska angle could be a good hook, and what she’d read of the story so far was a fun romp in the Alaskan wilderness with a GI and a local tomboy of a gal. The earnestness in the author’s words showed how serious she was about wanting others to fall in love with Alaska like she had.

Compared to what Dottie had just read, though, the Alaskan romance felt flat. But at least it would have an ending. And at least she knew something about the author. Even without the benefit of the cover letter, Dottie was always able to pick up an… understanding of the writer as she read their work.

Whenever Dottie read, it was like she got brief glimpses into the mind of the author. It had always been that way for her, even when she was a little girl. She’d thought everyone felt and knew these kinds of things and only slowly realized that they didn’t as she got older.

Immersed in a story, Dottie could tell the author’s gender, even when the given name was just a first initial. She could tell if they were writing from their own experience, if they were inspired by reading about something, or if they were making everything up for the sheer love of it. She could even tell how the author felt when they were putting pen to paper.

The knowledge just came to her, a mist of understanding that crept in from the edges of the page when she took in the story. Sometimes insight rolled in quietly, becoming more dense with detail the further she read. Other times the flashes came in fast and intense: lighting from a thunderstorm that blew in on an otherwise sunny day.

As a young girl, Dottie had learned that some of the saddest people wrote the funniest prose. Those who were the most fearful of the world wrote the bravest characters and those who were lonely wrote about family and love like no one else.

Fumbling to light a cigarette, Dottie looked over at her friends passing the pages of the new story among themselves. She watched the three of them, trying to grasp why and how the author of the unfinished stories was different from every other writer whose work she’d read. She took a long drag from her cigarette, held it between her pursed lips and straightened the pages of the Alaskan story that she’d thrown aside when she’d run to answer Bobby’s call.

It was easier to let herself fall back into the swirling eddy of details that she picked up on from the young romance author, rather than to try in vain to make guesses about the mysterious writer.

The Alaskan author was a young transplant from a different area, probably in her late teens. When Dottie read her work, she could feel the younger woman’s appreciation for Alaska: not as a first home, but as an adopted homeland. Dottie also intuited the girl was from a military family. The bits about the GI rang true and were written with ease and confidence, handled in a way that no amount of research alone could produce. As for her age, Dottie felt the girl’s youth in her moments of self-consciousness when it came to the romance, which she had very little personal experience with.

Oh, and the author was used to being an outsider of sorts, in a way that extended beyond being a military kid. Dottie couldn’t put her finger on exactly how–not yet anyway–but felt she would be able to by the end of the story.

Yet when it came to the writer who never finished a story, Dottie could barely pick up anything about them. She didn’t know if they were a man or a woman, what their emotional state was as they wrote, or anything else. Not even the smallest detail presented itself to her when she read the author’s words. She wasn’t used to having to guess at things.

©Sarah Tollok 2024

BOOKSTORIES is now available everywhere books are sold. Reprinted with permission from Balance of Seven Press. Find out more here at www.balanceofseven.com

WWPH NewS

On May 16, we will officially publish AGUAS/WATERS by Uruguayan poet Miguel Avero and translated by Jona Colson. This is the first in our new Washington Writers’ Publishing House Translation Series. In July, Miguel Avero will be traveling to Washington, DC for readings at Politics & Prose (July 12 at the main store); The Ivy Bookshop in Baltimore (Happy Hour on Saturday, July 13), and at the Writer’s Center (on Sunday, July 14). Please join us! More information here. And a big shout out to Andrew S. Klein for designing the evocative cover!

.

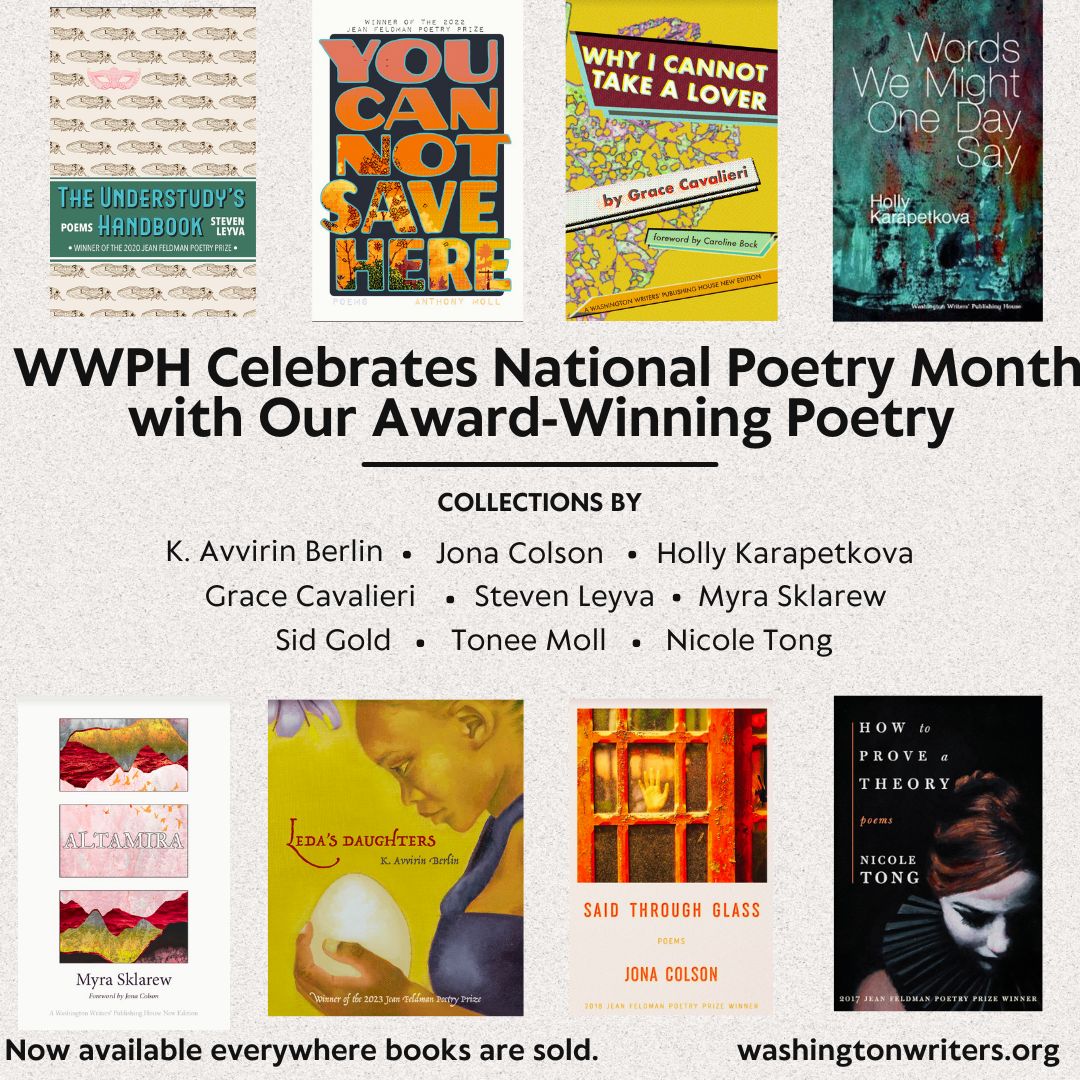

A Big Thank You to Dr. Jean Feldman for sponsoring our annual poetry prize!

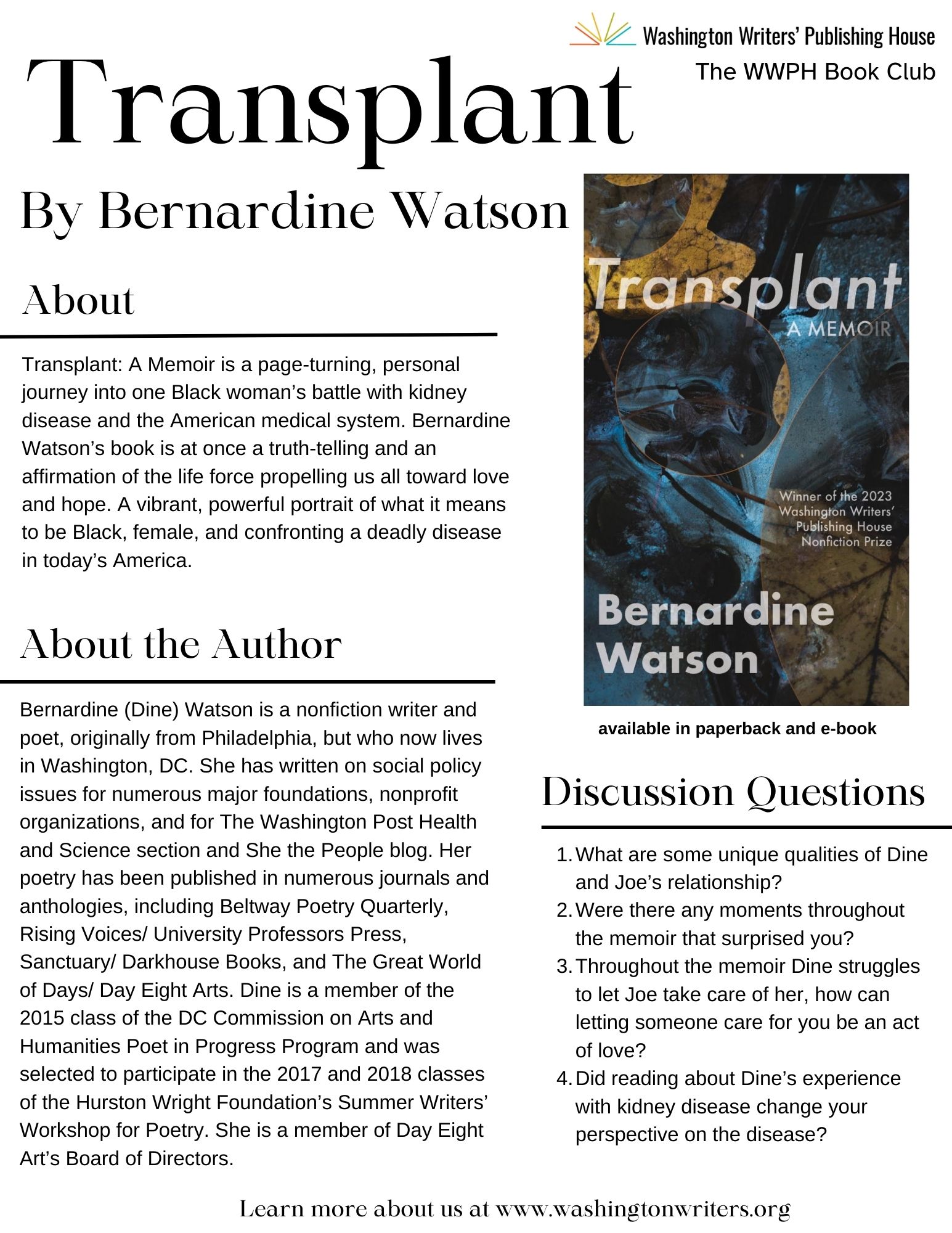

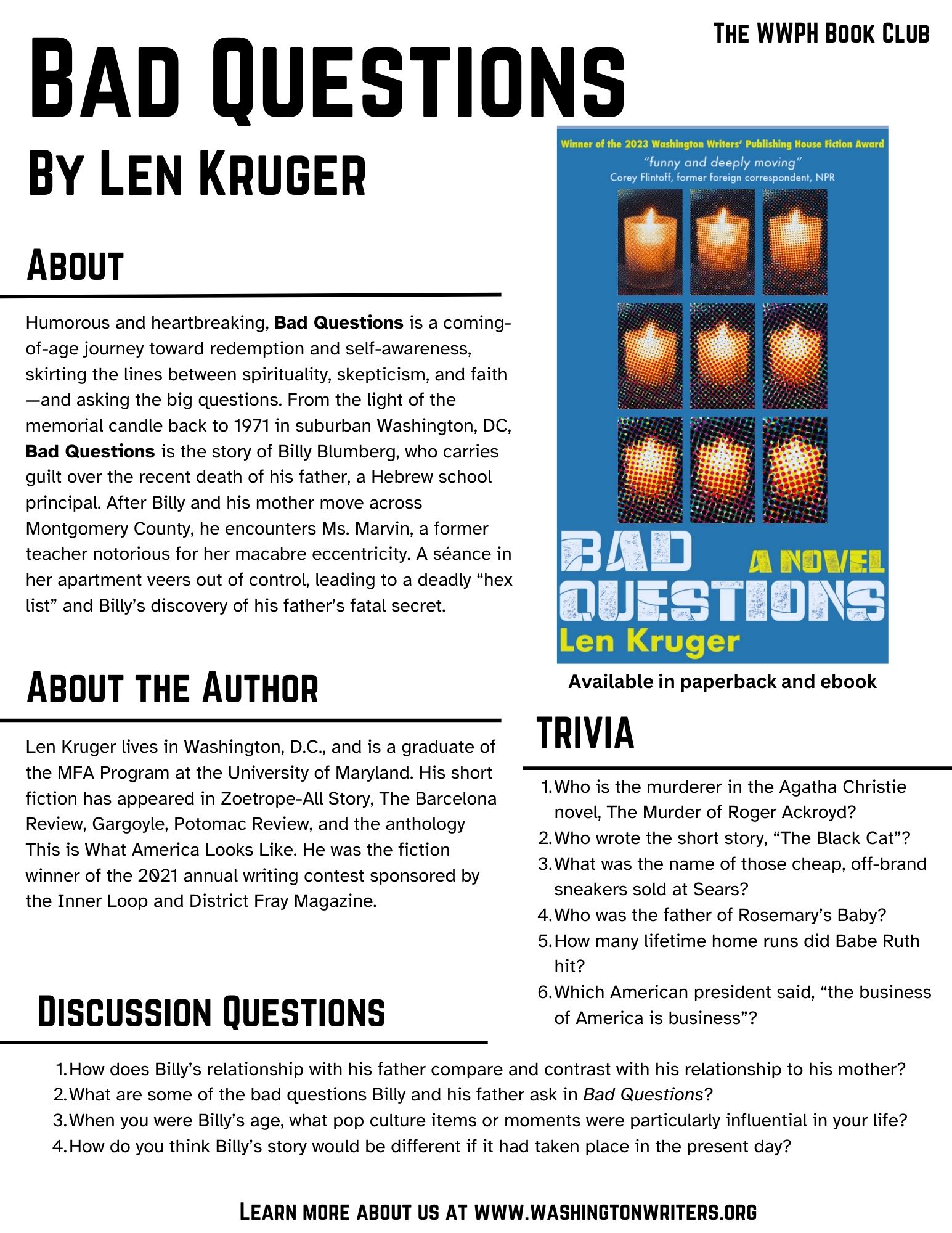

BOOK CLUBS. We have some nifty new reader’s guides for TRANSPLANT: A MEMOIR by Bernardine ‘Dine’ Watson and BAD QUESTIONS by Len Kruger. Big thanks to our outgoing WWPH Fellow, Alejandra Galdo, for these. Download them here!

SUBMIT to WWPH Writes. We are reading now for our summer issues. We are eager for new voices! We are an inclusive, writer-driven community and want to see your poetry and prose (1,000 words or less). Free to submit. Send us your work via our Submittable link here. Insider news: we are planning our annual WWPH PRIDE contest with cash prizes and publication. This year, PRIDE will have a special call for allies of the LGBTQ+ community. Look for WWPH PRIDE to open in May. And for those asking about our annual TINY POEMS special summer issues–yes, they are returning in August! Insider news: we will be seeking tiny odes! Keep reading WWPH Writes for details.

Our 2023 Award-Winning Books continue to garner attention and acclaim. They are available everywhere books are! Support your local independent bookstore and your WWPH by ordering them from www.bookshop.org. And our classic ebooks are now on sale!