WWPH Writes: Issue # 36

Welcome to Issue 36!

We are thrilled to share two excerpts from debuts by DMV writers, both intertwined with beauty and mystery along with haunting lyricism. The first work, a poem from Sarah Katz’s daring collection, Country of Glass, transports us back to the 1940s. A short excerpt from Virginia Hartman’s acclaimed novel, The Marsh Queen, opens at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in DC. with Loni Murrow, an accomplished bird artist, and tantalizes us with what might come next. (This reader is already reading more of The Marsh Queen.)

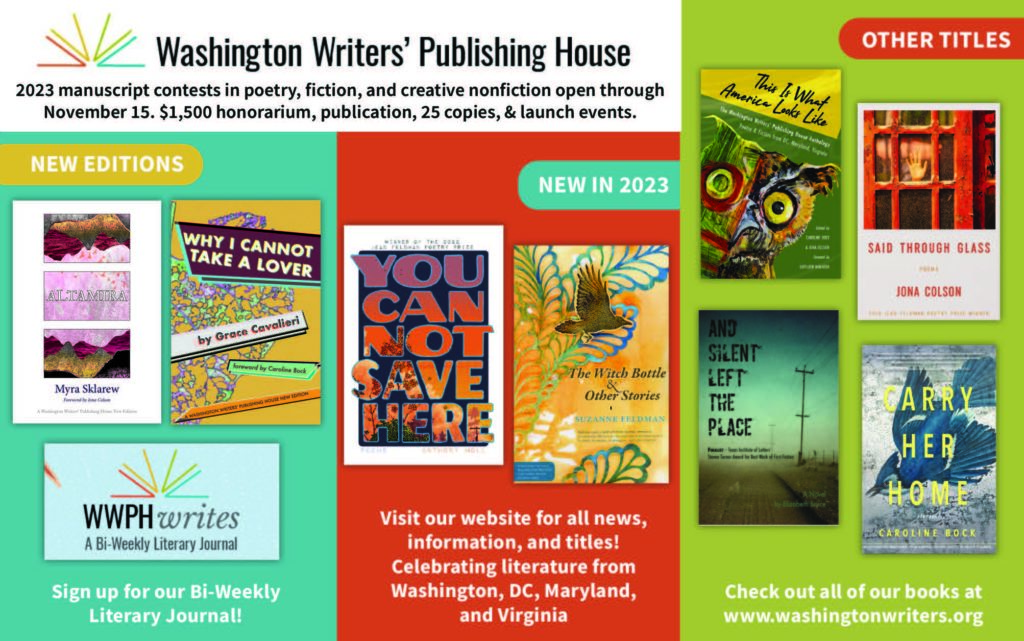

Some news to share: we are offering a new WWPH Fellowship opportunity. See below for details! We also are extending the deadline for our 2023 manuscript contests to November 15th. We are eager to read your book-length manuscripts in poetry, fiction, or creative nonfiction. More details here. Lastly, we hope to see you in Frederick, Maryland this weekend as we continue our 2022 award-winning DMV book tour with Suzanne Feldman and Anthony Moll (Sunday, October 30th at 3 pm at Gravel and Grind. Details here.)

Read on!

Caroline Bock

co-president/fiction editor

WWPH Writes: Poetry

Sarah Katz is the author of Country of Glass (Gallaudet University Press, May 2022). She holds an MFA in creative writing from American University, where she teaches. Her poems appear in Bear Review, District Lit, Hole in the Head Review, Redivider, RHINO, Right Hand Pointing, Rogue Agent, the So to Speak blog, The Shallow Ends, and Wordgathering, among others. Her essays and articles have appeared in The Atlantic, Business Insider, The Guardian, OZY, The Nation, The New York Times, The Rumpus, Scientific American, Slate, The Washington Post, and other publications. Sarah is the Poetry Editor of The Deaf Poets Society, an online journal that features work by writers and artists with disabilities. Purchase a copy of COUNTRY OF GLASS at Gallaudet University Press site here and everywhere books are sold.

PORTRAIT OF A BROTHER AND SISTER, 1940

She rides turtles across Siberian tundra.

Children shout in Polish from passing cattle cars.

Her brother strikes an angry driver with his gun,

who falls to the ground, mouth frothing like a dog’s.

Run, he shouts to her with a coyote’s eyes

narrow as dark seeds.

Her brother chases her to Kazakhstan wielding

a snake stick. Yellow eyes stalk them at night.

She is six. By twelve, she knows seven languages,

memorizes Aleksander Pushkin, sings operettas

in French and German. In New York, she shapes

new sounds with her tongue. Always,

her brother’s stick follows closely.

© Sarah Katz 2022

WWPH Writes: Fiction

Virginia Hartman earned an MFA in creative writing from American University and is on the faculty at George Washington University. She also teaches at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda. Her stories have been shortlisted for the New Letters Awards and the Dana Awards, and she’s a proud contributor to the Potomac Review, Beltway Poetry Quarterly, Sligo Journal, Washingtonian, Delmarva Review, and Blue Bird City. The Marsh Queen is her first novel. Find out more at VirginiaHartman.com. Purchase THE MARSH QUEEN here and everywhere books are sold.

THE MARSH QUEEN

Context from the novelist:

Loni Murrow is an accomplished bird artist at the Smithsonian. But when she receives a call from her brother summoning her home to help their mother recover after an accident, Loni’s contained life in Washington, DC, is thrown into chaos, and she finds herself back by the Florida marsh that reminds her of her father. Pulled between her professional accomplishments in Washington and the small town of her childhood, Loni must decide whether to delve into murky half-truths and either avenge the past or bury it.

The following is an excerpt from Chapter 2, and has been edited for length.

The public space of the museum is loud and full of tourists. Their curiosity is endearing—they’re acolytes for the natural world. But on my gray days, entering the building carries the weight of the deaths of all the specimens: carcasses of every species, stuffed or otherwise retrieved from oblivion so we can know them, yet all dead. On these days, my defense is to imagine every pinned butterfly taking wing, every stuffed marsupial waking up, every preserved plant specimen blooming and carpeting the floor like a time-lapse forest, and every bird coming to life, flying up to the dome and away.

Thus lifted, I can lose myself for hours drawing, for instance, the common loon, with its inky head and an intricacy of pin dots cascading across the wings. With the right precision, I can bring the deadness of a bird skin to a striking facsimile of life.

I enter the back hallway and ascend to my studio, a well-lit office with my drafting table by the window. Vertical shelves hold drawing papers arranged by weight and soft pencils organized by the pliability of their graphite. Dark bottles of Rapid Draw sit next to an insanely large number of pen nibs and, next to them, my tubes of paint in rainbow order, ROYGBIV and all the gradations between.

I sit at my drafting table and look out over the National Mall and its line of American elms, soon to begin a fragile March budding, and toward the Smithsonian Castle. I’ve worked here for nine years, but it only took one day at Natural History to know I’d found my home. Yesterday was my thirty-sixth birthday, and my colleagues came in singing, insisting I blow out candles on a cake. They don’t know the water is rising as I close in on thirty-seven, my father’s magic number, his end point.

On my slanted table is a partially finished Vanellus chilensis, the southern lapwing, her slender black crest flying out behind her head. I refine the bronze sheen on the wings and fill in the gray, black, and white of the face.

I’m at the tip of the beak when the phone rings.

“Loni, it’s Phil.”

For a millisecond I think my brother has remembered my birthday. Then I come to my senses. “Phil, is something wrong?”

“Mom’s had a fall. You gotta get here.” He pauses. “And . . . you should plan for an extended stay.” He tells me she broke her wrist, but that’s not the main problem. “She’s been acting strangely, Loni. Her memory—”

“Come on, everybody that age forgets things,” I say. I was home last year and noticed her extra-short temper with me, but that’s just an intensification of a lifelong habit.

“Tammy thinks it’s the early-onset thing.”

My mother’s only sixty-two, and Phil’s wife, Tammy, is no medical expert. I don’t want my sister-in-law making any diagnoses. “I’ll see if I can get some days off.”

“No, listen, Loni. Take more. This is major. And we need you here.”

He so rarely asks. However, it’s not the ideal time to miss work. The incoming administration has installed a cadre of nonscientists, mostly baby business majors, to examine the Smithsonian’s efficiency quotient. I’d call them fresh young faces if they weren’t so imperious and sour. Ornithology’s youthful hatchet man is Hugh Adamson. Last Monday, he called a meeting to spit out corporate-speak. “We’ll be encouraging early retirement,” he said to his elders. “We won’t replace those who quit, and we’ll enforce any violations of the leave policy. Downsizing via attrition,” he paused, “should not affect morale.”

I head down the hall to consult the botany librarian, Delores Constantine, who’s worked at the Smithsonian for the last forty years. The passage leading to Botany is lined with cabinets full of dried plants laid out on acid-free paper. Today, I imagine them as a vertical garden, orchids and epiphytes dripping from the sides, a phantom scent of humid forest.

I enter the library. “Delores?”

“Back here.”

She stands on a rickety stool between stacked bookshelves. At eye level, the hem of her mauve skirt meets a pair of age-spotted shins. She lifts two large volumes above her head and hoists them onto a high shelf. She can be as prickly as a stalk of blessed thistle, so I don’t mention the danger of her perch. When she steps down, I tell her about my brother’s call, and the need to take time off.

She crosses to her desk, clicks the mouse, and peers at the screen. “This is the FMLA form. Family Leave.” She whips a sheet off the printer, offering it to me with a blue-veined hand. “You fill this out, ask for eight weeks off, and go take care of your mom.”

“Eight weeks? No possible way.”

“You don’t have to use it all. Heck, the law gives you twelve. But with all the suits walking around this place, best keep it to eight.”

“Two weeks in my hometown would be more than I can take,” I say.

Delores puts a stack of books onto a cart. “You ask for eight, and if you use only two, come back and look incredibly dedicated to your work.”

As a plant person, Delores may not seem like the most apt career counselor for a bird artist, but she knows more than anyone about how this place works.

“So,” she says, “go fill out that form and walk it down to HR.”

As I reach the doorway, she lifts another set of books and says, “Three things to remember: Number one, the Smithsonian won’t pay you during your family leave.”

“But—”

“Number two, check out the liaison program. I think the Tallahassee Museum is a subscriber. If they pay you directly, you can preserve your leave status.”

I nod, then turn back. “What’s number three?”

“Don’t go a minute past the time you request. It’s the French Revolution around here, and they’re oiling the guillotine.”

Reprinted from THE MARSH QUEEN by Virginia Hartman. Copyright © 2022 by Virginia Hartman. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. more information about this acclaimed debut including a book club reading guide here. Photo credit: Danielle Prince.

WWPH Community News

More details on our 2022 books and our 2023 Manuscript Contests here.

*NEW! WWPH FELLOWSHIP OPPORTUNITIES! The new WWPH Fellowship provides the opportunity for undergraduates and graduate students, or anyone with a keen interest in the literary small publishing world, to get hands-on experience working with a nonprofit literary press. WWPH Fellows will learn small press publishing from WWPH executive board members and authors while helping advance the press’s mission. Each fellow will receive a $500.00 stipend in return for three to four hours of remote work over a ten-week fellowship session supervised by your WWPH co-presidents Caroline Bock and Jona Colson. Deadline: DECEMBER 6th. More details and how to apply here. Questions? email us at wwphpress@gmail.com and subject line: WWPH Fellowship. Shout out to Dr. Jean Feldman for underwriting this new initiative!

*Big shout out of thanks to The Inner Loop, a fabulous literary arts organization in Washington DC! The Inner Loop featured our 2022 award-winning authors Suzanne Feldman and Anthony Moll in their Author’s Corner this month and highlighted them and their WWPH books in their reading series, podcast, postcards, and more here.

*SUBMIT TO WWPH WRITES! We are seeking poetry and prose that celebrate, unsettle, and question our lives in the DC, Maryland, and Virginia areas (DMV) and our nation. We seek lyrical and dynamic work and believe in cultivating a diverse and inclusive environment of content, form, risk, and experimentation. New perspectives and voices with craft and fierceness are strongly encouraged to submit. It’s FREE to submit, but you must live in the DMV. We are reading right now for January 2023 — if you have something that will inspire us for the new year– Submit here.

The WASHINGTON WRITERS’ PUBLISHING HOUSE has a Bookshop! BUY OUR AWARD-WINNING BOOKS and help us keep this nonprofit, cooperative, literary press strong for writers and readers like you. Click here and browse all our titles at our bookshop.

Thank you for being part of the WWPH Community! Have a Safe and Fun Halloween!

Caroline Bock

Fiction Editor, WWPH Writes

President, WWPH

Jona Colson

Poetry Editor, WWPH Writes

President, WWPH