WWPH WRITES ISSUE 67- SPECIAL AWP ISSUE

Welcome to Issue 67… and works that transport us far beyond the ordinary, Astrolabe, a poem by David Keplinger, and The House of Plain Truth, a novel excerpt by Donna Hemans.

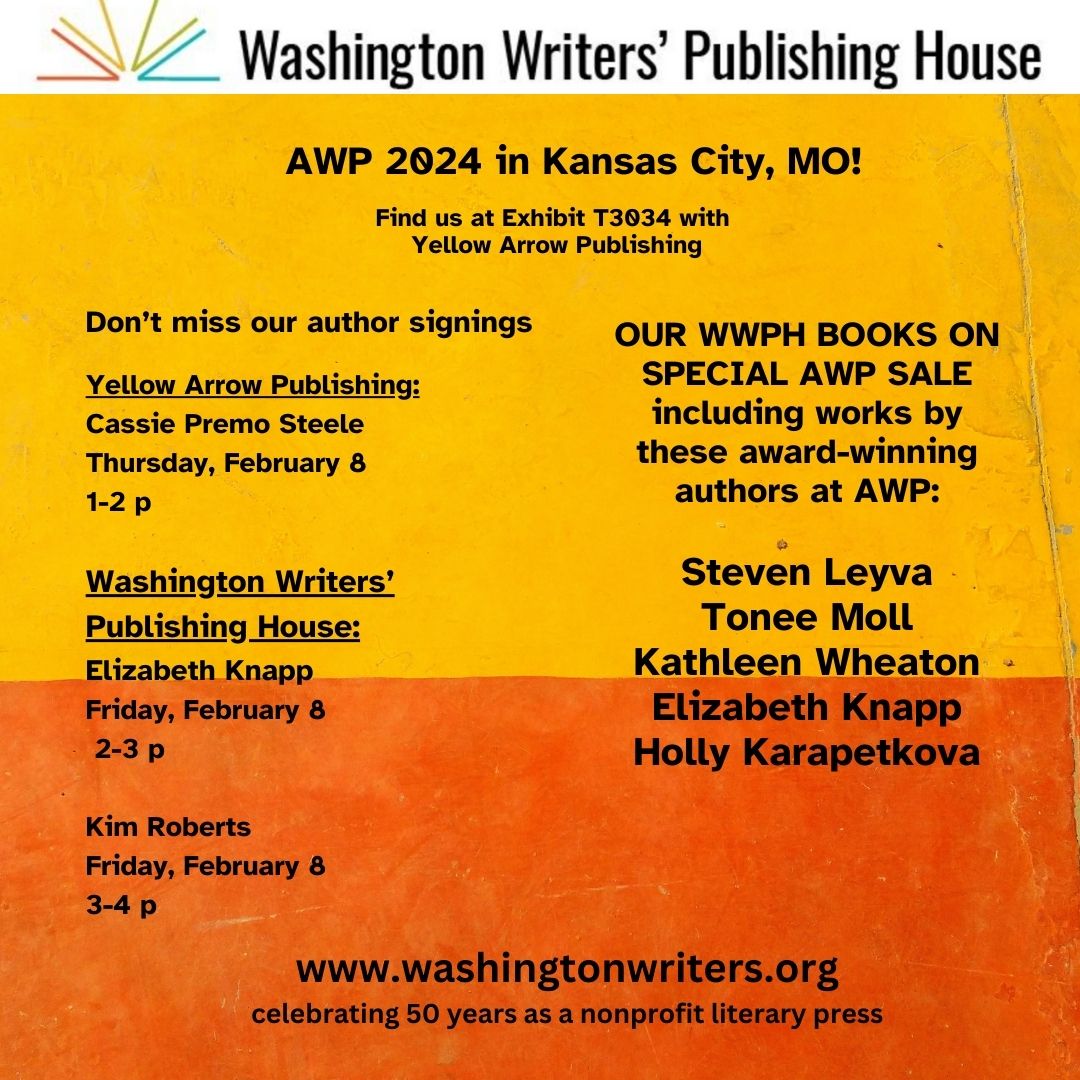

We are excited to have the Washington Writers’ Publishing House at AWP in Kansas City this week. Stop by our exhibit table (T3034) and say hello to Kathleen Wheaton and Holly Karapetkova, our fiction and poetry vice presidents. All our WWPH books are on sale for AWP!

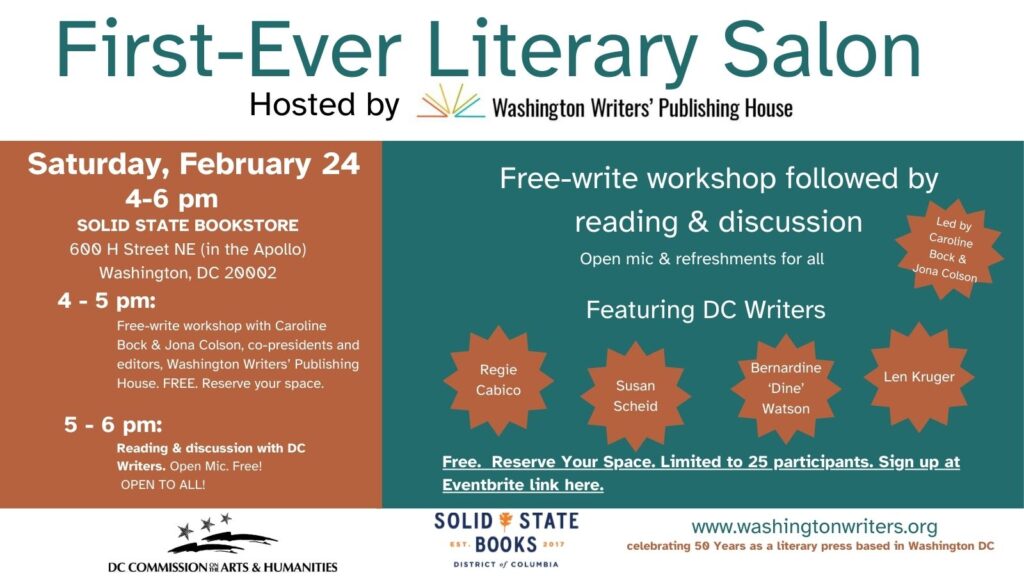

Plus, this February, we will also be at the MoCo Underground (February 15) at the Sandy Spring Museum in Maryland and our first-ever WWPH LITERARY SALON (February 24) with Solid State Books in Washington DC, made possible with a grant from the DC Commission on the Arts & Humanities. Lastly, we have a special treat for you–a cover reveal of our first-ever book in translation, Aguas/Waters by Miguel Avero, with Jona Colson as a translator.

Read on!

Caroline Bock & Jona Colson

co-presidents, WWPH

WWPH WRITES POETRY

David Keplinger is the author of eight books of poetry, most recently Ice (Milkweed Editions, 2023) and Another City (Milkweed Editions, 2018), which won the 2019 UNT Rilke Prize. He’s the recipient of two fellowships from the NEA, the Colorado Book Award, The Emily Dickinson Award from the Poetry Society of America, and the T.S. Eliot Award. David directs the MFA Program in Creative Writing at American University.

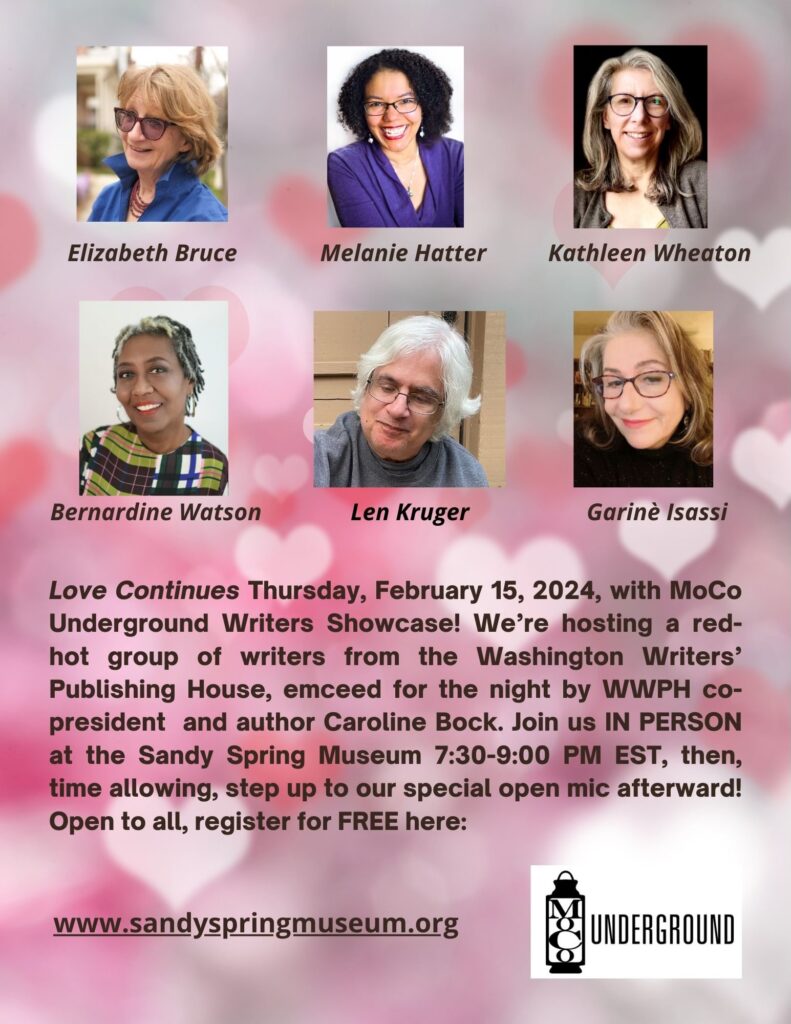

ASTROLABE It had been used to measure azimuths for a thousand years before Vermeer painted it onto the tablecloths of The Astronomer. Out of Persia, it is for seeing myths, but much has been concealed here—vast distances along the mater, the layered discs whose purposes were squandered, whose uses for the hajj have been lost. On the globe in front of him, the stars are portrayed as animals from legend. They do not lurch (there is nothing to defend) when he tests that melon with his fingers.

©David Kelpinger 2024

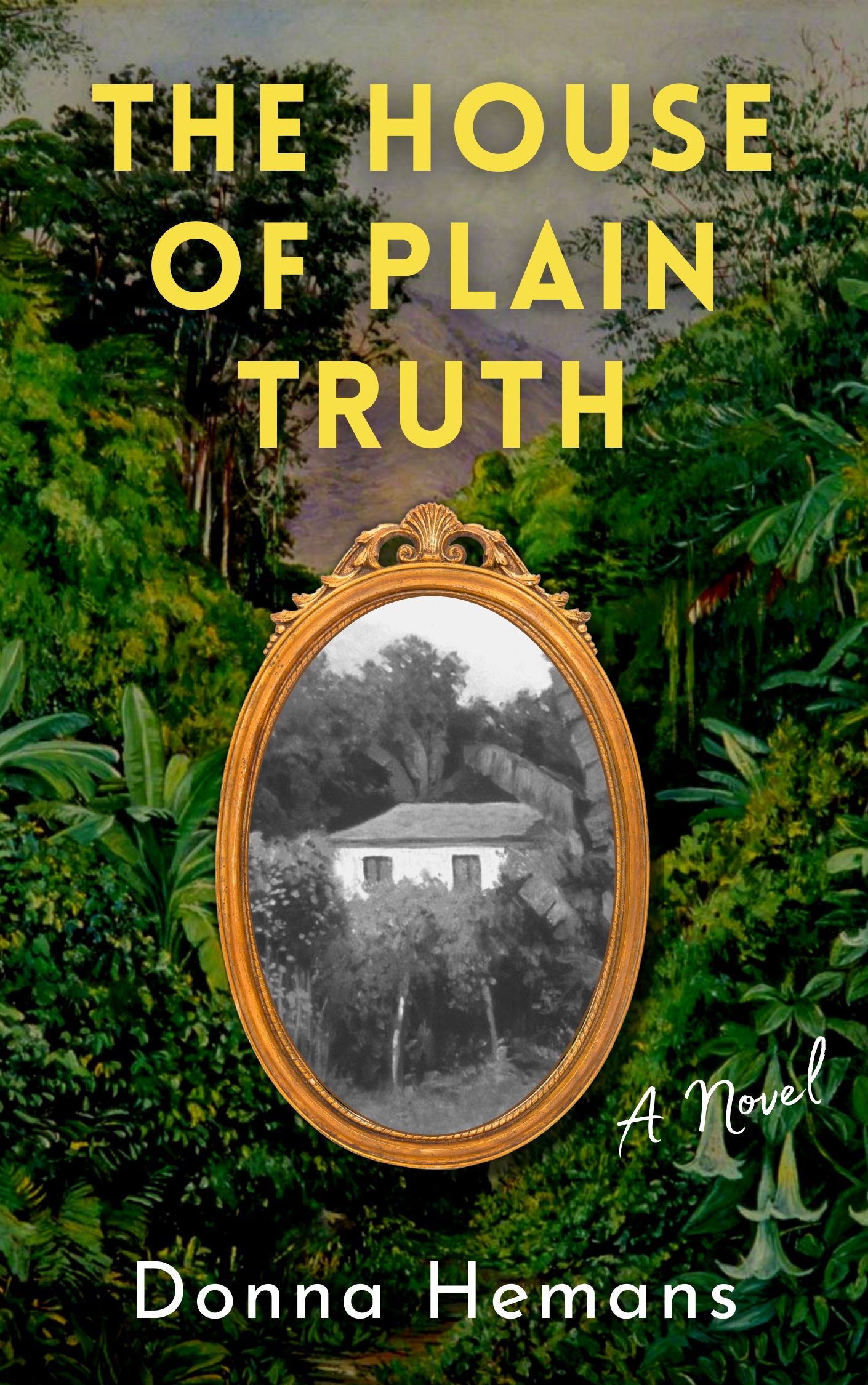

WWPH WRITES: A NOVEL EXCERPT

Donna Hemans is the author of two previous novels, River Woman and Tea By the Sea, which won the Lignum Vitae Una Marson Award. Her short fiction and essays have appeared in Electric Literature, Ms. Magazine, and Crab Orchard Review, among others. She is also the owner of DC Writers Room, a co-working studio for writers based in Washington, DC. Born in Jamaica, she lives in Maryland, and received her undergraduate degree in English and Media Studies from Fordham University and an MFA from American University. Photo credit: Shala W. Graham.

From the author on this excerpt:

“The House of Plain Truth is the story of Pearline Greaves who envisions a quiet, settled retirement in her family home in Jamaica. Upon her return to Jamaica, her dying father, Rupert, asks her to be his memory and to find her siblings, who the family hasn’t heard from in nearly sixty years. Not only does Pearline have to carry out her father’s wishes, she has to contend with her sisters who are trying to sell the family home. In the scene below, Pearline is at her father’s graveside and beginning to contemplate how her new life is not quite what she imagined.”

It’s late afternoon when the caravan of cars turns off the main road and the passengers trek past the house, past the semicircle of citrus plants and another half circle of croton plants to the small family cemetery in the clearing behind the house. The croton plants’ variegated leaves flutter above the open pit where the pallbearers and funeral home attendants will lower Rupert’s casket. Red dirt is banked around the hole, and looking at it now, Pearline feels the tears she has been holding back welling up. She steps away from the gravediggers—sweat-stained and tired—who stand to the side, waiting to finish their task; away from the mourners who crowd in, leaving only a small space for family; away even from those reaching out to pat her arm or attempting to draw her into an embrace.

Instead of stopping, Pearline waves tentatively, brushes her fingers against a woman’s open and sweaty palm, pats another woman on her shoulder, and keeps walking.

“That the second daughter,” Pearline hears a woman say. “She live a foreign now.”

Pearline’s sisters Aileen and Hermina remain up front, flanked on either side by their children, grandchildren, and husbands. Aileen, taller, thinner, holds her head down. Hermina, in distinct contrast, is shorter, squat, and holds her back straight, head up, exposing every tear, every sputter. Pearline stays back, too tearful to watch the final lowering of the casket or sing the mournful hymns. Near Pearline, someone starts singing, “Soon and very soon, we are going to see the king. No more crying now, we are going to see the king . . .”

The crowd picks up the song, singing louder and louder, bodies swaying as gently as leaves in the breeze. Every now and then someone claps, trying to maintain the beat, but that peters out quickly, and the moment remains solemn. Under the canopy of trees, it feels as if each song rises and stops, settles above and around the group, shutting out the rest of the living world.

As soon as that song ends, another begins, one running so smoothly into the other that it feels practiced, feels as if this entire group of people simply goes from funeral to funeral like a choir hired to mourn the dead. Now that Pearline is here in the yard of her childhood home, away from the church and no longer standing near the altar with her back to the full congregation, she can look around and take stock of who has come, the faces from the past that she remembers, the members of the community whose lives she knows nothing about, Aileen’s and Hermina’s friends and coworkers whom she may never see again. Once, she could recite everyone’s story, point to a house, and say, “Mattie mother build that house after the hurricane of ’51,” point to a child and say, “Lenny granddaughter,” or hear a cock crowing and know the neighbor’s yard where the sound originated. The names don’t come as easily now, and the faces, weathered by years and circumstances, make it hard for Pearline to figure out who’s who. But this game, matching faces and names and attempting to tag both to long-ago events, helps take her mind off the funereal hymns, the finality of the burial.

Pearline waits for the ping of dirt hitting the casket and steps back even farther outside the canopy, behind the row of croton plants this time. She doesn’t want to see the final closure of the grave, doesn’t want to hear the dirt raining down on the casket, doesn’t want to hear the shovels mixing and scooping concrete. She’s stood through

this portion of a burial only once—for her mother. That time, she was near the place where her sisters now stand, just behind her father, who knelt next to the hole in the ground and watched the final sealing off of a life. Pearline and Hermina had knelt with him too, their arms draped around his back. Aileen stood behind him, ready to hold him back if necessary. Even now, Pearline feels the contractions of his midsection, his muscle and bone convulsing beneath her fingers, the untamed emotion wracking his body. It had frightened her then, that unfiltered display she had never seen in him. Her father, so stoic and stubborn in his daily life, came apart at his wife’s graveside. The sound of shovels mixing concrete stayed with Pearline too, and from there on out, each time she hears that sound, she remembers her father kneeling in the dirt, crying, talking through his tears as if his wife were sitting on the other side hearing him out.

He had held up a hand too, momentarily stopping the gravediggers from filling in the hole. “Mi just wan’ say one last thing.” He choked out the words, and the men stopped their movements, waiting for the grieving husband to say his final goodbye. Sound fell away. The immediate surroundings were so quiet, it felt as though life itself were gone and the three of them had been transported elsewhere. Her father leaned forward, not dipping his head toward the casket that was already settled in the hole but jutting his head as if he saw Irene sitting directly across from him on the other side of the grave. His eyes didn’t waver from that single place. Pearline moved her hand from his back to his arm, uncertain if he would topple forward onto the casket, ready to grab at him if he leaned too far forward. They sat like that for what seemed like a long while, the solemn hymns rising up around them, until at last Irene’s siblings stepped forward and slowly began dribbling dirt onto the casket.

This time Pearline can’t get far enough away. Each hymn seems louder, and she thinks of the hymns as vines wrapping themselves around her body, not comforting but choking and causing her grief to spill without control. Pearline cries for her father, for her daughter Josette and the granddaughters she left behind in New York. She cries for this new life of hers as a returned resident who gave up her life in America and came back home just in time for her father’s last week alive. Only two weeks old, this new life she’s carving out is already shifting. Mostly, Pearline cries because she knows her daughter will never mourn her as Pearline mourns her father now or as her father once mourned her mother. And what, she asks herself, is the meaning of this life if she isn’t mourned or remembered at the very end?

Excerpted from THE HOUSE OF PLAIN TRUTH by Donna Hemans © 2024, used with permission from Zibby Books. Now available everywhere books are sold. More at Zibby Books here.

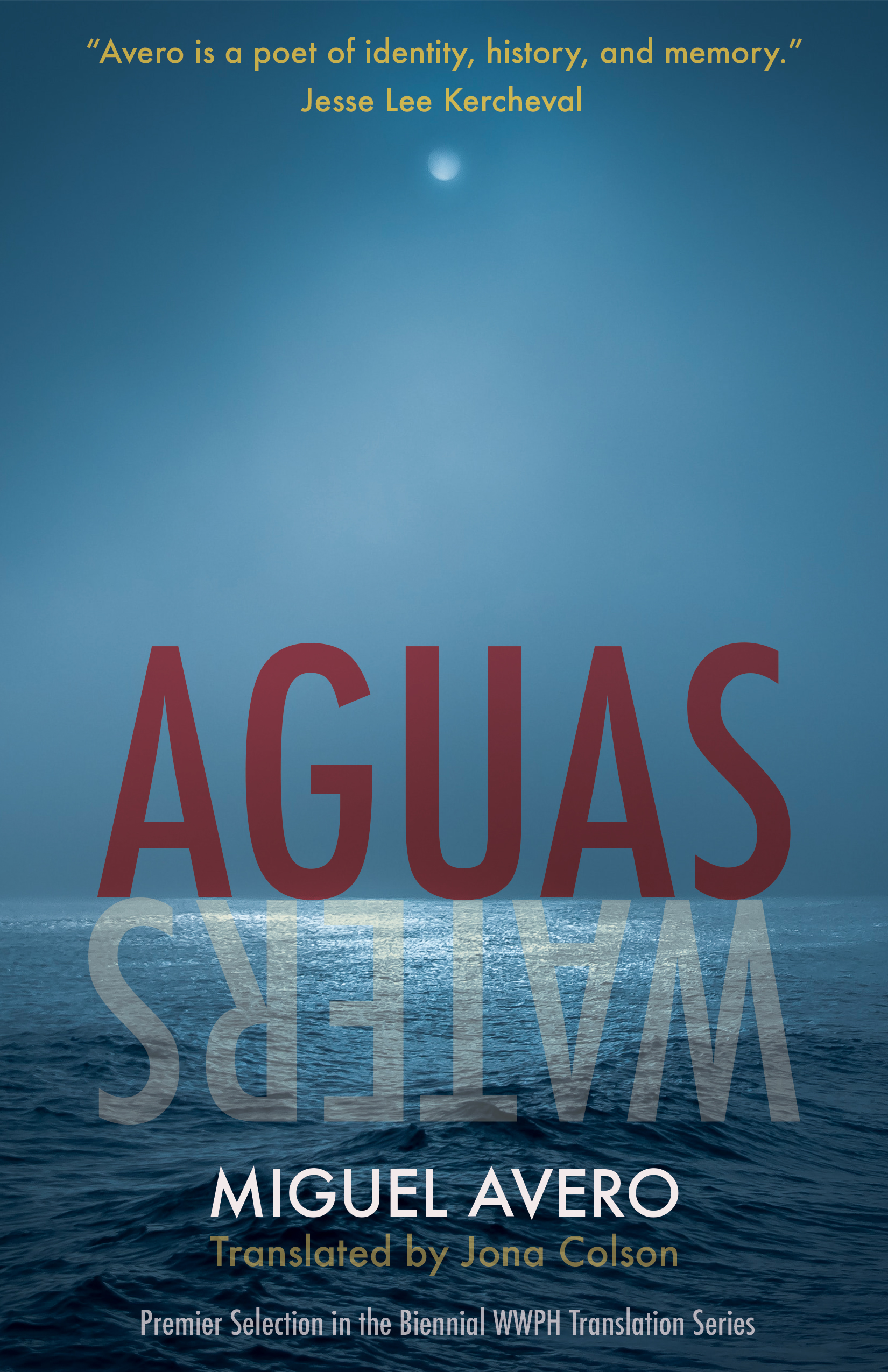

WWPH SPECIAL COVER REVEAL

Aguas/Waters by Miguel Avero, translated by Jona Colson, will be published on May 16, 2024. Cover design by Andrew S. Klein. Ready for pre-order soon. More details on this poetry collection by this acclaimed Uruguayan author and our new WWPH works in translation initiative here.

WWPH NewS

JOIN US AT AWP in Kansas City on February 8-10! We’re excited to return to AWP after a number of years. Find our exhibit table with Yellow Arrow Publishing at #T3034. The WWPH Books at our table on special sale!

And on February 15th, don’t miss our WWPH Reading with the MoCo Underground:

Our First-Ever Literary Salon promises to be an exciting, creative, literary event. Please join us for our creative writing workshop. Our goal is to write four short pieces together on the theme of “Writing with Purpose.” These will be guided workshops with prompts and writing samples led by our writers. You will have a chance to share your work in our small group workshop, or even at our open mic. Spots for the workshop from 4-5 pm are limited to the first 25 registrants. However, there is no limit for the reading and panel discussion from 5-6 pm. Join us at Solid State Books on Saturday, February 24th. Reserve your space here. Questions? Please email us at wwphpress@gmail.com. A big thank you to the DC Commission of the Arts & Humanities for their grant to WWPH for this event. And if you can’t make it on February 24, we are doing a second Literary Salon in July!

For our readers in Maryland… from our friends at the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore. FREE POETRY CONTEST for Maryland residents age 18 and older sponsored by Enoch Pratt Free Library and Little Patuxent Review. Deadline: March 1, 2024. The winning poem will be published in Little Patuxent Review and celebrated at a public reading. For complete guidelines, see prattlibrary.org/poetry-contest

SUBMIT to WWPH Writes. We are reading now for our late spring issues. We are eager for new voices! We are an inclusive, writer-driven community and want to see your poetry and prose (1,000 words or less). Free to submit. Send us your work via our Submittable link here.